The Commissioner went away, taking three or four of the soldiers with him. In the many years in which he had toiled to bring civilization to different parts of Africa he had learnt a number of things. One of them was that a District Commissioner must never attend to such undignified details as cutting down a dead man from the tree. Such would give the natives a poor opinion of him. In the book which he planned to write he would stress that point. As he walked back to the court he thought about that book. Every day brought him some new material. . . . There was so much else to include, and one must be firm in cutting out details (147-48).

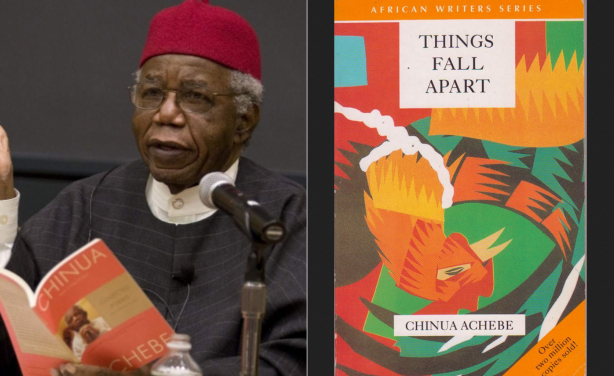

The passage above comes from the last paragraph of Chinua Achebe’s most-read work, Things Fall Apart. It contains one of the many brilliant arguments marshalled in this world-renowned book that has generated the highest number of critics and critiques. With that deft and pithy stroke, Achebe reveals the sheer arrogance of the colonial enterprise masquerading as leadership as well as argues that the hitherto largely unchallenged representation of Africans by European writers is spurious. By admitting that “There was so much else to include . . . [but] one must be firm in cutting out details,” the Commissioner—who is an exemplar of European imperialism—shows that his prospective The Pacification of the Primitive Tribes of the Lower Niger is unreliable and biased. The palpable overarching argument that Achebe makes is that all Europeans who have ever written about Africa, whether in fictionalized forms or pure history, are false authorities whose works should not be trusted.

The Commissioner’s choice of words is also worth noting. He speaks of “the many years in which he had toiled to bring civilization to different parts of Africa” as though it were an obligation or duty. Indeed, it is worse than that. As Ipshita Chanda points out in “Hawk and Eagle: Cultural Encounters and the Philosophy of ‘Understanding’ in Achebe’s Narratives,” it is more of an obsession. She recalls how one of the champions of Enlightenment, the ideological movement that footed the enterprise of colonialism on a strong philosophical and moral basis, had pictured a Utopia that Enlightenment was sure to deliver; for Immanuel Kant, to think of the Enlightenment phenomenon as a mere European happening was ridiculous. Enlightenment was a universal or, even more correctly, “human” phenomenon:

Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-incurred immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one’s own understanding without the guidance of another. . . .[L]aziness and cowardice are the reasons why such a large population of men, even when nature has long emancipated them from alien guidance, nevertheless so gladly remain immature (103-104).

It is no surprise then that the District Commissioner wears a similar attitude for he is a conveyor of this Enlightenment good news to the distant dark world of Africa. Laura Kunreuther traces out the strong connection between the Enlightenment and colonialism. Quoting Nicholas Dirk, an anthropologist, she writes:

“Colonialism provided a theatre for the Enlightenment project,” writes Dirk. “Science flourished in the eighteenth century not merely because of the intense curiosity of individuals working in Europe, but because colonial expansion both necessitated and facilitated the active exercise of the scientific imagination. . . . Even history and literature could claim vital colonial connections, for it was through the study and narrativization of colonial others that Europe’s history and culture could be celebrated as unique and triumphant (77).

Things Fall Apart has won Achebe worldwide recognition, and he has been called the inventor of modern postcolonial literature. Simon Gikandi writes of him: “Achebe is the man who invented African literature because he was able to show, in the structure and language of [Things Fall Apart], that the future of African writing did not lie in simple imitation of European forms but in the fusion of such forms with oral traditions” (xvii). Recognizing that Things Fall Apart is “an exercise in historical recuperation,” Richard Begam writes in “Achebe’s Sense of an Ending: History and Tragedy in Things Fall Apart”:

. . .Achebe writes a form of nationalist history. Here the interest is essentially reconstructive and centers on recovering an [African] past that has been neglected or suppressed by historians who would not or could not write from an African perspective. . . . Nationalist history tends to emphasize what other histories have either glossed over or flatly denied.

Throughout the pages of Things Fall Apart, Achebe alludes to the inaccuracy of African representation by European authors and stresses that, as Begam quotes, “African people did not hear of culture for the first time from Europeans; that their societies were not mindless but frequently had a philosophy of great depth and value and beauty, that they had poetry and, above all, they had dignity” (397).

As many critics have also noted, Achebe rewrites the African history “without romanticizing the African past” (Gikandi, xii). Indeed, in Things Fall Apart Achebe portrays the lead character, Okonkwo, as an overwhelmingly flawed being. Even though he is a hero and a “proud and imperious emissary of war” who is “treated with great honour and respect” (09) by his people, he is not infallible; often, his errors have grave consequences. Indeed, Okonkwo’s divergent views on family relationships, leadership, and colonialism counter traditional Igbo mores and precipitate the ultimate disintegration of the tribal Igbo community in the face of British imperialism.

Works Cited

Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. Exp. ed. with notes. Oxford: Heinemann, 1996. Print. African Writers Series. Classics in Context.

Begam, Richard. “Achebe’s Sense of an Ending: History and Tragedy in Things Fall Apart.” Studies in the Novel 29.3 (1997): 396 – 411. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 17 Oct. 2012.

Chanda, Ipshita. “Hawk and Eagle: Cultural Encounters and the Philosophy of ‘Understanding’ in Achebe’s Narratives.” Philosophia Africana 9.2 (2006):101 – 16. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 17 Oct. 2012.

Gikandi, Simon. “Chinua Achebe and the Invention of African Literature.” Things Fall Apart. By Chinua Achebe. Exp. ed. with notes. Oxford: Heinemann, 1996. ix –xvii. Print. African Writers Series. Classics in Context.

Kunreuther, Laura. “‘Pacification of the Primitive’: The Problem of Colonial Violence.” Philosophia Africana 9.2 (2006): 67-82. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 17 Oct. 2012.