While there are a significant number of people who do not feel positive about the deeds of the white man, none suggests violence. The thoughtful Obierika thinks such an act will not be wise: “It is already too late. . . . Our own men and our sons have joined the ranks of the stranger. They have joined his religion and they help to uphold his government” (124). Being his typical self, Okonkwo calls for immediate war to cleanse the land. He boasts of how Umuofia is immeasurably greater than the clan that the white man has wiped out: “We would be cowards to compare ourselves with the men of Abame.

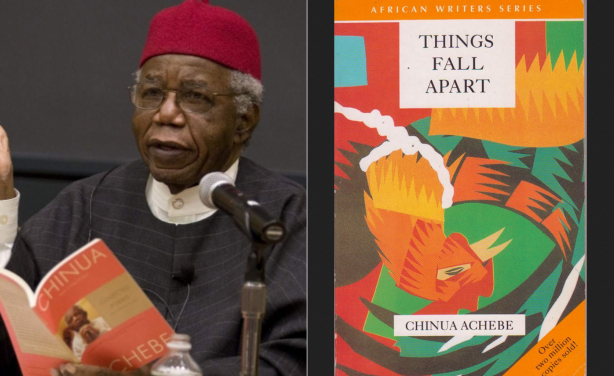

Achebe Rewrites Africa’s History: The Glorious “Primitive Tribes” (Part 3)

Achebe portrays Okonkwo as having a non-representative faulty view of leadership

Okonkwo’s view of leadership is simply deficient. Not only is he very prone to irrational behaviour, but he also does irrational things because of his view on gender roles. Driven by fear of being seen as weak and a failure, like Unoka, Okonkwo deifies masculinity. His primary motivation, “to hate everything that his father Unoka had loved,” includes hating “gentleness.” He thinks gentleness is a feminine or agbala trait. As mentioned en passant earlier, it is this extreme view on masculinity that encouraged him to kill his adopted son. This is also the reason he thinks his closest friend is a coward. Besides, Okonkwo is also psychologically unstable. As Polycarp Ikuenobe, an Igbo critic, points out, “In order to achieve [leadership], an individual must be ‘psychologically wholesome,’ emotionally and rationally stable, communally well adjusted, and must consistently show excellent judgment” (125). If this “Ikuenobian” requirement were a sacrosanct litmus test for leadership, Okonkwo would be nowhere close to passing it. Okonkwo has an emotional instability syndrome; in fact, it seems like his overall phenotype bears witness to this condition. Achebe writes about Okonkwo:

Achebe Rewrites Africa’s History: The Glorious “Primitive Tribes” (Part 2)

Achebe Portrays Okonkwo As Having a Non-representative Faulty View of Family Relationships

The tribal Igbo community of Okonkwo has its mores that every child learns as it grows up. A man is the head of his family meaning that he is the primary provider. The people’s staple food is yam, and “Yam, the king of crops, was a man’s crop” (16) because it requires a lot of muscular work over a relatively long period to grow it. When the harvest comes, the man feeds his family primarily from the produce; it was a subsistent kind of farming. As Achebe emphatically reiterates, “Yam stood for manliness, and he who could feed his family on yams from one harvest to another was a very great man indeed” (24). Often the woman helps the man by growing “women’s crops, like coco-yams, beans and cassava” (16) alongside with him. It is, however, the woman who typically runs the house since the man often spends most of the hours on the farm. Achebe writes, for instance, about Okonkwo that “During the planting season Okonkwo worked daily on his farms from cock-crow until the chickens went to roost” (10). She ensures that the family meals are prepared in time, teaches the kids family values, make sure the house constantly have enough water to run on, and represents the man in absentia. Above all, the woman respectfully and lovingly submits to the man as the head of the house.

Achebe Rewrites Africa’s History: The Glorious “Primitive Tribes” (Part 1)

The Commissioner went away, taking three or four of the soldiers with him. In the many years in which he had toiled to bring civilization to different parts of Africa he had learnt a number of things. One of them was that a District Commissioner must never attend to such undignified details as cutting down a dead man from the tree. Such would give the natives a poor opinion of him. In the book which he planned to write he would stress that point. As he walked back to the court he thought about that book. Every day brought him some new material. . . . There was so much else to include, and one must be firm in cutting out details (147-48).