Achebe Portrays Okonkwo As Having a Non-representative Faulty View of Family Relationships

The tribal Igbo community of Okonkwo has its mores that every child learns as it grows up. A man is the head of his family meaning that he is the primary provider. The people’s staple food is yam, and “Yam, the king of crops, was a man’s crop” (16) because it requires a lot of muscular work over a relatively long period to grow it. When the harvest comes, the man feeds his family primarily from the produce; it was a subsistent kind of farming. As Achebe emphatically reiterates, “Yam stood for manliness, and he who could feed his family on yams from one harvest to another was a very great man indeed” (24). Often the woman helps the man by growing “women’s crops, like coco-yams, beans and cassava” (16) alongside with him. It is, however, the woman who typically runs the house since the man often spends most of the hours on the farm. Achebe writes, for instance, about Okonkwo that “During the planting season Okonkwo worked daily on his farms from cock-crow until the chickens went to roost” (10). She ensures that the family meals are prepared in time, teaches the kids family values, make sure the house constantly have enough water to run on, and represents the man in absentia. Above all, the woman respectfully and lovingly submits to the man as the head of the house.

Having a distorted view of what it means to be a man and father, and this being engendered by his childhood experience, “Okonkwo [rules] his household with a heavy hand” (09). His father, Unoka, becomes a pariah towards the end of his life partly because he is struck by a disease but also because he was an agbala. All these happenings make the puerile mind of Okonkwo wrongly associate his father’s shortcomings with that of fatherhood. Unoka becomes the exact antithesis of Okonkwo’s life “[and] so Okonkwo was ruled by one passion—to hate everything that his father Unoka had loved” (10). Thus, whereas Unoka is a gentle, cheerful being who loves his people and family, Okonkwo beats his own family and would not vacillate to “pounce on people” (03) when the opportunity presents itself. So deep in his mind is this misconception that Okonkwo would not “stop beating somebody half-way through, not even for fear of a goddess” (21). Such is the act that makes him break the sanctity of the Week of Peace when he pounces on his wife for not cooking his food in time—an act for which he duly pays. It is worth noting that Okonkwo, who apparently lacks self-control, could have cut short his life by this sacrilegious act because, as Ogbuefi Ezeudu points out, the penalty for such a thing used to be fatal: “My father told me that he had been told that in the past a man who broke the peace was dragged on the ground through the village until he died” (23). Nwoye is the other unfortunate recipient of Okonkwo’s raw fury. At the sight of what he sees to be “incipient laziness” (10) and “[too] much of his grandfather” (46), Okonkwo tries to nurture Nwoye into a man of his own image—through incessant nagging and beating. Indeed, it seems like he is going to achieve that goal until he takes away Nwoye’s adopted brother. The last straw that breaks the camel’s back is the event that takes place after Nwoye’s affiliation with the Christians is discovered:

Nwoye turned round to walk into the inner compound when his father, suddenly overcome with fury, sprang to his feet and gripped him by the neck.

‘Where have you been?’ he stammered.

Nwoye struggled to free himself from the choking grip.

‘Answer me,’ roared Okonkwo, ‘before I kill you!’

He seized a heavy stick that lay on the dwarf wall and hit two or three savage blows. (107)

Had Okonkwo not kill Ikemefuna, he ostensibly would not have had to lose his firstborn child because “[Ikemefuna] was like an elder brother to Nwoye, and from the very first [encounter] seemed to have kindled a new life in the younger boy.” Nwoye is developing into the very chap that his father has always wanted him to become. The boy was letting go of some of his “grandfather” that was in him. He “no longer spent the evenings in [his] mother’s hut while she cooked, but now sat with Okonkwo in his obi, or watched him as he tapped his palm tree for the evening wine” (37). When Okonkwo kills Ikemefuna, however, he unknowingly gives Nwoye another reason to become a dissident—first, at heart. It is, thus, Okonkwo’s distorted view of how a family should be run that ruined him first; his views run counter to those of the majority of his constituent.

It is unbecoming enough that Okonkwo does not have a popular understanding of how to be the head of a family; it is worse that, though he is “one of the greatest men of his time,” he also does not have a good grasp of what leadership—as understood by his society—is all about. It is true that among his people, “achievement [is] revered,” (06) but there is another side to the coin of leadership as conceived of by tribal Igbo community; a leader is rational and analytical. Obierika is perhaps the best character that illustrates this leadership quality. After Okonkwo had killed Ikemefuna, he goes to visit Obierika wondering why his friend did not come along to do the bidding of the Oracle:

‘I cannot understand why you refused to come along with us to kill that boy,’ he asked Obierika.

‘Because I did not want to,’ Obierika replied sharply. ‘I had something better to do.’

It is worth noting that whereas Okonkwo’s understanding of leadership is one necessarily subservient to the gods, Obierika’s is one where he retains his will and reasoning regardless of what the gods say. Obierika even dares to say that he “had something better to do” than doing the will of a god. Okonkwo then momentarily forgets that the man he is talking to is an achiever like himself which was why they became friends in the first place—since Okonkwo “[has] no patience with unsuccessful men”(03)—and wrongly concludes that Obierika is a coward:

‘But someone had to do it. If we were all afraid of blood, it would not be done. And what do you think the Oracle would do then?’

Obierika has to remind him: “You know very well, Okonkwo, that I am not afraid of blood; and if anyone tells you that I am, he is telling a lie” (46).

Apparently, these two leaders do not have the same understanding. Obierika is more analytical and sound in his judgment. As he pointedly argues, “if the Oracle said that my son should be killed I would neither dispute it nor be the one to do it” (47).

Work Cited

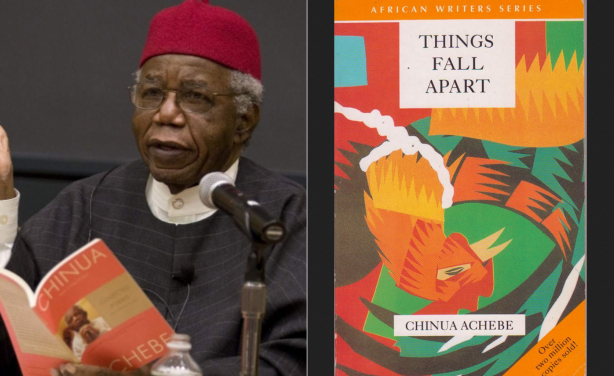

Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. Exp. ed. with notes. Oxford: Heinemann, 1996. Print. African Writers Series. Classics in Context.