Achebe portrays Okonkwo as having a non-representative faulty view of leadership

Okonkwo’s view of leadership is simply deficient. Not only is he very prone to irrational behaviour, but he also does irrational things because of his view on gender roles. Driven by fear of being seen as weak and a failure, like Unoka, Okonkwo deifies masculinity. His primary motivation, “to hate everything that his father Unoka had loved,” includes hating “gentleness.” He thinks gentleness is a feminine or agbala trait. As mentioned en passant earlier, it is this extreme view on masculinity that encouraged him to kill his adopted son. This is also the reason he thinks his closest friend is a coward. Besides, Okonkwo is also psychologically unstable. As Polycarp Ikuenobe, an Igbo critic, points out, “In order to achieve [leadership], an individual must be ‘psychologically wholesome,’ emotionally and rationally stable, communally well adjusted, and must consistently show excellent judgment” (125). If this “Ikuenobian” requirement were a sacrosanct litmus test for leadership, Okonkwo would be nowhere close to passing it. Okonkwo has an emotional instability syndrome; in fact, it seems like his overall phenotype bears witness to this condition. Achebe writes about Okonkwo:

He was tall and huge, and his bushy eyebrows and wide nose gave him a very severe look. He breathed heavily, and it was said that, when he slept, his wives and children in their out-houses could hear him breathe. When he walked, his heels hardly touched the ground and he seemed to walk on springs as if he was going to pounce on somebody. And he did pounce on people quite often. He had a slight stammer and whenever he was angry and could not get his words out quickly enough, he would use his fists (03).

About the only Ikuenobian quality one could say that Okonkwo possesses, arguably, would be being “communally well adjusted.” He is so fearsome that “His wives, especially the youngest, lived in perpetual fear of his fiery temper, and so did his little children” (09). Summarizing Okonkwo’s divergent and deficient view on leadership, Chanda notes:

Okonkwo laboured under the delusion that his society desired from him a rigid masculinity. It was, in fact, not his society that exacted this self-definition from him but his own personal history. Okonkwo’s mistake, pointed out to him again and again by his peers and by elders, was to hierarchize genders, privileging the masculine over the feminine, valorizing the former and belittling the latter. (112)

Achebe Portrays Okonkwo as having a divergent view on colonialism

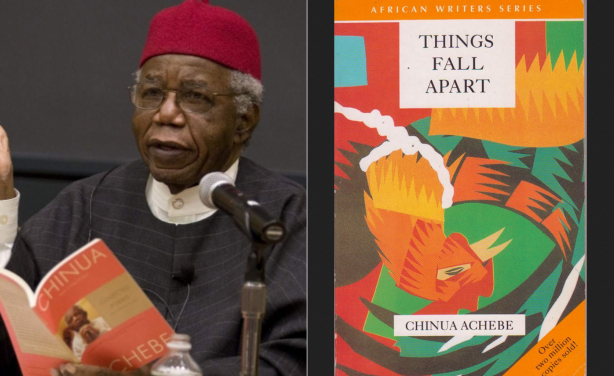

Many critics, especially non-African ones, readily note that Things Fall Apart is “an exercise in historical recuperation.” Carey Snyder, for instance, concurs that “. . . [Things Fall Apart] aims to wrest from the colonial metropole control over the representation of African lives, staking a claim to the right to self-representation” (155). A striking observation, however, is the somewhat unanimous proclivity of these critics not to challenge the accuracy of Achebe’s representation of Africa. The history of Nigeria supports the depiction of colonialism in Things Fall Apart. As Don C. Ohadike notes, “European slave traders had exported substantial numbers of Igbo people from the Bight of Biafra to the New World. Nonetheless, no European had penetrated the interior of Igboland before 1830” (xxxix). It should be recalled that the United Kingdom touched off abolition of slavery politics when the nation realized “that the slave trade was no longer consistent with [her] economic interests,” (xxxix) in the 1830’s and that America followed suit in the 1860’s. A passage in Things Fall Apart supports this view. After the clan of Abame has been wiped out, Obierika, while retelling the story to Okonkwo who is on exile, says “We have heard stories about white men who made the powerful guns and the strong drinks and took slaves away across the seas, but no one thought the stories were true” (99). The people did not believe the account because they had never seen a white man before. That the people never saw a white man supports the view that no white man had ever “penetrated the interior of Igboland.” Ohadike continues, “While the abolition debate raged on, however, certain interest groups in Europe and America formed societies to push European cultural, commercial, and political influence into African interior” (xxxix)—thus was born the genesis of the exodus of Europeans into the interior of tribal Igbo community.

Christian missionaries played a very huge role in the invasion of Igbo land, argues Ohadike. They were the first Europeans to gain access into the core of Igbo society in fairly large numbers. As they trooped inwards, they took along their foreign ideals that ultimately clashed with the people’s mores. Their reports of the African ways of life to their home governments spurred European imperialism, continues Ohadike (xli). This is the picture depicted on the latter pages of Things Fall Apart, and these inaccurate reports were what European writers heavily relied on in writing about Africa. An interesting historical fact that Ohadike mentions is “that many of the most effective [Christian] missionaries were, in fact, Africans” that were either born to former slaves or are ex-slaves. Achebe alludes to this when he writes that an interpreter of the white man is an Ibo man and that three other members of the white man’s company speak Ibo (102).

The tribal society’s general disposition towards the colonial officials is ambivalent. Though the white man “put[s] a knife on the things that held” (125) the people together, but he also helps to improve the economy of the land by his trading with the people such that “for the first time palm-oil and kernel became things of great price, and much money flowed into Umuofia” (126). This realization and the soft-treading, mutually respectful style of Christianity that Mr Brown practices ministers to the soul of the “many men and women in Umuofia who [do] not feel as strongly as Okonkwo about the new dispensation” (126). So potent is this happening that even a high-ranking title-holder, Ogbuefi Ugonna, “like a madman had cut the anklet of his titles and cast it away to join the Christians” (123). Even the unyielding and unconvinced Akunna, who never stops having protracted ontological and epistemological discourse with Mr. brown, releases one of his sons to attend the Christian school. He seems struck by “something vaguely akin to method in the overwhelming madness” (126) that has visited the community. The white man’s religion seems to make sense. “From the very beginning,” Mr Brown ensures that “religion and education [go] hand in hand” (128). Nevertheless, a number of people including Obierika do not feel good about this development.

Works Cited

Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. Exp. ed. with notes. Oxford: Heinemann, 1996. Print. African Writers Series. Classics in Context.

Ikuenobe, Polycarp. “The Idea of Personhood in Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart.” Philosophia Africana 9.2 (2006): 117 – 31. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 22 Oct. 2012.

Ohadike, Don C. “Igbo Culture and History.” Things Fall Apart. By Chinua Achebe. Exp. ed. with notes. Oxford: Heinemann, 1996. xix-xlix. Print. African Writers Series. Classics in Context.

Snyder, Carey. “The Possibilities and Pitfalls of Ethnographic Readings: Narrative Complexity in Things Fall Apart.” College Literature 35.2 (2008): 154 – 74. MLA International Bibliography. Web. 17 Oct. 2012.