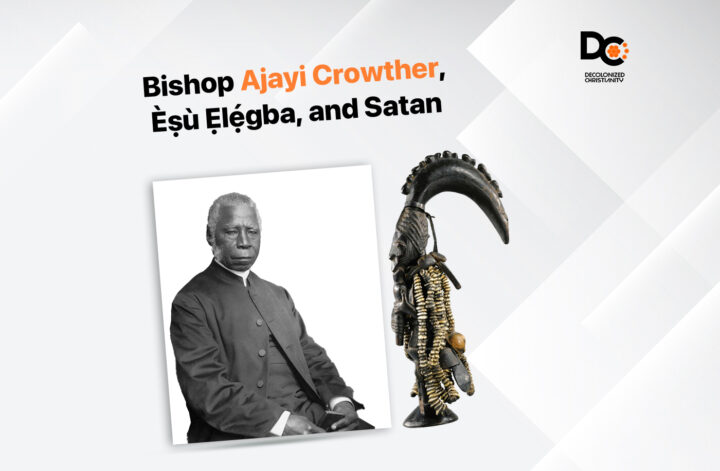

We have told the story of Bishop Ajayi’s early life. The teenage Ajayi was captured by his compatriots and sold into slavery. But for the interception of a British squadron, Ajayi would have been sold in the trans-Atlantic slave trade and might never have been known—just like the innumerable millions who perished in that grand evil scheme. It is hard to imagine that Ajayi, especially as he would later have learned about what could have been, would not have felt like he owed his life to Britain. Not only was he saved by British sailors, but he was also educated and introduced to Christianity by British missionaries. Considering the history of Britain at the time, we may assume that racist and hegemonic inclinations tainted the Christian education he received. So, it should not be shocking if we find vestiges of Eurocentrism in Crowther’s works. What should be more critical is what Crowther willfully believed and defended.

Èṣù Ẹlẹ́gbara and the Evolution of Satan (Series Part 2)

Èṣù in Yoruba Metaphysics: A Brief Note

Traditionally, the Yoruba conceive of the world as an interconnected three-tiered cosmos: Ọ̀run (meaning, heaven), Aiyé (meaning, the earth), and Ilẹ̀ (meaning, underground; netherworld). Ọlọ́run (literally, “heaven’s owner”) inhabits Orun, the Yoruba pantheon’s realm, alongside over four hundred gods, many of whom walked the earth as humans with supernatural abilities. Ọlọ́run, also known as Ẹlẹ́dàá (literally, “the creator”), is the supreme being. Aiyé is the world of humans, and Ilẹ̀ is the world of departed souls, especially of ancestors. The dividing wall between Ọ̀run and Ilẹ̀, especially regarding deified souls, is quite ethereal.

Bishop Ajayi Crowther and the Yorùbá Bible (Series Part 1)

Background

Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther’s contributions to African Christianity are well attested in the Christian world, especially in the Global South. In his native land, however, the Bishop is mainly seen as a villain than a hero. He is seen as an able instrument of colonialism used to undermine Yoruba metaphysics. His significant achievement, a Yoruba version of the Bible, is critically described as a courier of “Euro-Christian ideas, beliefs, and cultural logics” (Adefarakan, 45) written in the Yoruba language. Among the adherents of the traditional Yoruba religion, Bishop Crowther is a traitor who willfully allowed himself to be used in the corruption of what he once held dear.

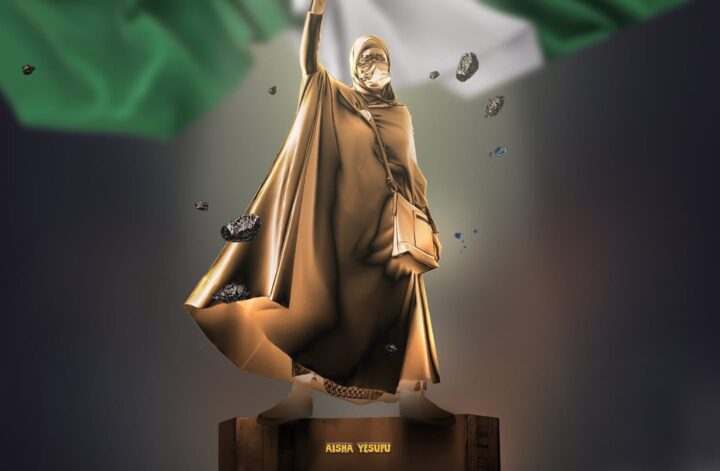

Reflections on the State-Sponsored Lekki Shooting and a Way Forward

On October 20, 2020, the Nigerian Government almost broke my brain as it did my heart when it sent out its historically reliable instrument of evil, the Nigerian Army, against peaceful protesters in Lekki, Lagos, and other parts of the country. It was a day reminiscent of the era of dictators in the execution of orders, and the resulting chaos was apocalyptic in spirit. It destabilized me. I could not even motivate myself to read source materials, let alone write–though I have a list of subjects that I would like to explore. That was a day never to be forgotten. Interestingly, the days leading up to October 20 were quite inspiring in the raw display of human togetherness that politicians have slowly led Nigerians to believe no longer exists. There were moments of intense pride and even of proto-patriotism. Bravery was displayed for all to see. In this piece, I want to focus primarily on how we may proceed from here.

Sàngó and the Aláàfin: Ancient Yorùbá Use of Religion in Politics

Background

Sàngó’s story belongs to the very beginning of the Yorùbá nation, which is believed to have been founded by Odùduwà after migrating from “the East” to Ilé-Ifè. According to Samuel Johnson, Odùduwà might have originated from somewhere near modern-day Sudan or Egypt (5). People lived in the land before Odùduwà and his entourage got there (Johnson, 18); indeed, Odùduwà met Setilu, the father of Ifá worship, in the land (4). As is true of all empires, not all the people in the Ọ̀yọ́ empire were originally natives. Many of the different tribes that self-identify as Yoruba today likely had ancestors who identified differently. As Odùduwà and his army advanced, they absorbed natives of the land into the dominant culture of proto-Yorùbá. As I shall show later, the narrative fed to an empire’s people can be a powerful political tool that confers a common identity and solidarity to a group of people.

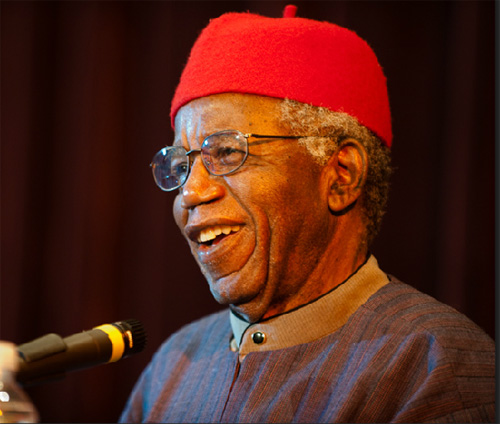

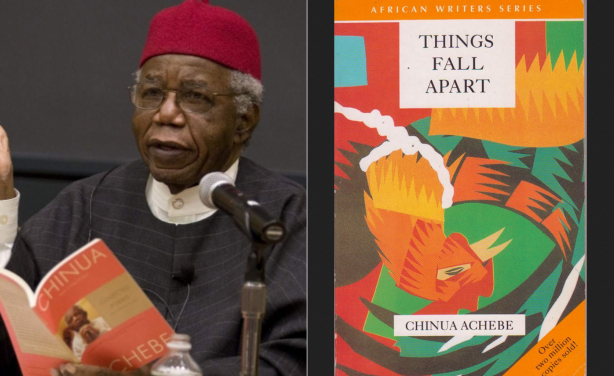

Achebe Rewrites Africa’s History: The Glorious “Primitive Tribes” (Part 4, Finale)

While there are a significant number of people who do not feel positive about the deeds of the white man, none suggests violence. The thoughtful Obierika thinks such an act will not be wise: “It is already too late. . . . Our own men and our sons have joined the ranks of the stranger. They have joined his religion and they help to uphold his government” (124). Being his typical self, Okonkwo calls for immediate war to cleanse the land. He boasts of how Umuofia is immeasurably greater than the clan that the white man has wiped out: “We would be cowards to compare ourselves with the men of Abame.

Achebe Rewrites Africa’s History: The Glorious “Primitive Tribes” (Part 3)

Achebe portrays Okonkwo as having a non-representative faulty view of leadership

Okonkwo’s view of leadership is simply deficient. Not only is he very prone to irrational behaviour, but he also does irrational things because of his view on gender roles. Driven by fear of being seen as weak and a failure, like Unoka, Okonkwo deifies masculinity. His primary motivation, “to hate everything that his father Unoka had loved,” includes hating “gentleness.” He thinks gentleness is a feminine or agbala trait. As mentioned en passant earlier, it is this extreme view on masculinity that encouraged him to kill his adopted son. This is also the reason he thinks his closest friend is a coward. Besides, Okonkwo is also psychologically unstable. As Polycarp Ikuenobe, an Igbo critic, points out, “In order to achieve [leadership], an individual must be ‘psychologically wholesome,’ emotionally and rationally stable, communally well adjusted, and must consistently show excellent judgment” (125). If this “Ikuenobian” requirement were a sacrosanct litmus test for leadership, Okonkwo would be nowhere close to passing it. Okonkwo has an emotional instability syndrome; in fact, it seems like his overall phenotype bears witness to this condition. Achebe writes about Okonkwo:

Achebe Rewrites Africa’s History: The Glorious “Primitive Tribes” (Part 2)

Achebe Portrays Okonkwo As Having a Non-representative Faulty View of Family Relationships

The tribal Igbo community of Okonkwo has its mores that every child learns as it grows up. A man is the head of his family meaning that he is the primary provider. The people’s staple food is yam, and “Yam, the king of crops, was a man’s crop” (16) because it requires a lot of muscular work over a relatively long period to grow it. When the harvest comes, the man feeds his family primarily from the produce; it was a subsistent kind of farming. As Achebe emphatically reiterates, “Yam stood for manliness, and he who could feed his family on yams from one harvest to another was a very great man indeed” (24). Often the woman helps the man by growing “women’s crops, like coco-yams, beans and cassava” (16) alongside with him. It is, however, the woman who typically runs the house since the man often spends most of the hours on the farm. Achebe writes, for instance, about Okonkwo that “During the planting season Okonkwo worked daily on his farms from cock-crow until the chickens went to roost” (10). She ensures that the family meals are prepared in time, teaches the kids family values, make sure the house constantly have enough water to run on, and represents the man in absentia. Above all, the woman respectfully and lovingly submits to the man as the head of the house.

Achebe Rewrites Africa’s History: The Glorious “Primitive Tribes” (Part 1)

The Commissioner went away, taking three or four of the soldiers with him. In the many years in which he had toiled to bring civilization to different parts of Africa he had learnt a number of things. One of them was that a District Commissioner must never attend to such undignified details as cutting down a dead man from the tree. Such would give the natives a poor opinion of him. In the book which he planned to write he would stress that point. As he walked back to the court he thought about that book. Every day brought him some new material. . . . There was so much else to include, and one must be firm in cutting out details (147-48).

Changing Destinies: Incoherence in Yoruba Thought?

Àyànmọ́ mi láti ọwọ́ Olúwa ni

Ẹ̀dá ayé kan kò lè ṣí mi nípò padà

Ẹ̀lẹ̀dá mi yé mo bẹ̀bẹ̀ yé

Ẹ̀lẹ̀dá mi gbé mi lékè ayé.

This piece is from a famous track of the legendary Juju maestro, Ebenezer Obey. Roughly translated, the stanza says:

My destiny is from God

No human can change my destiny

Oh, my Head (Creator), I plead

My Creator, help me to be victorious over evil people.