On October 20, 2020, the Nigerian Government almost broke my brain as it did my heart when it sent out its historically reliable instrument of evil, the Nigerian Army, against peaceful protesters in Lekki, Lagos, and other parts of the country. It was a day reminiscent of the era of dictators in the execution of orders, and the resulting chaos was apocalyptic in spirit. It destabilized me. I could not even motivate myself to read source materials, let alone write–though I have a list of subjects that I would like to explore. That was a day never to be forgotten. Interestingly, the days leading up to October 20 were quite inspiring in the raw display of human togetherness that politicians have slowly led Nigerians to believe no longer exists. There were moments of intense pride and even of proto-patriotism. Bravery was displayed for all to see. In this piece, I want to focus primarily on how we may proceed from here.

An anti-government protest must be absolutely peaceful. This is political wisdom first crystallized by Mahatma Gandhi and further popularized by the great US Civil Rights Movement leader, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The logic is simple: you hurt a government more by a peaceful protest than otherwise, and a government is more likely to dialogue with peaceful protesters. If the goal is to get the government to listen—that is, if the protesters are not seeking to secede—then a peaceful protest is the way to go. People protest against governments because of felt injustice or systemic inequality. In our case, the protest began as a call to end police brutality, a phenomenon that is so bad that, most times, it is indistinguishable from armed robbery violence. The injustice or inequality exists unchecked because some individuals, higher in government or leadership, are benefitting from it.

Now, given that the natural human tendency is to self-preserve when threatened, a typical government would rather ignore the calls and cries for as long as possible. It is as if the government has convinced itself that if it ignores the calls long enough, they will go away. And most calls and cries die out when the wronged persons become tired of crying. Hence, almost every Nigerian knows about someone who suffered police brutality or fatality with no redress. On rare occasions, however, the calls for change gather sufficient momentum, making it difficult for the government to keep ignoring it. Now, in world government history, there have been different ways that governments have attempted to address issues when it gets to this point. Almost always, a typical government seeks to crush the protests instead of trying to solve the issues raised. Sometimes, a government may pay a lip service or promulgate new laws that it does not intend to enforce. The goal is to disperse the protesters so that life can resume unchanged. The most potent weapon any (irresponsible) government, like General Buhari’s, craves at such times is the presence, or appearance, of violence among the protesters—it will not matter that the “violence” is sponsored if one has no evidence —because the government can then invoke its responsibility to maintain law and order to crush the protesters. Yes, actual violence would then quench what appeared to be violence among the protesters. At least, this was how events unfolded in the Lekki state-sponsored military shooting of unarmed protesters on October 20.

The ill-logic of violence in a protest ought to be obvious. Though riots and violence are often the means by which an oppressed group voices its dissatisfaction, violence will achieve nothing in changing the status quo. First, it is very unlikely that a protesting group within a nation would have better arms and members than the security agencies of a nation. In our case, a violently protesting group would be up against the Nigerian Security Forces (comprising all the military branches) and the police in all their factions. This would surely be an unwinnable battle. It also would be imprudent, especially if secession is not the goal. We should note, however, that the philosophy of peaceful protests is not necessarily opposed to self-defense. One may defend oneself against bullies and other troublemakers in one’s individual live. But, as Dr Martin Luther King argues in Where Do We Go From Here, an anti-government protest should not be formed around self-defense. Dr. King writes, “The question was not whether one should use his gun when his home was attacked, but whether it was tactically wise to use a gun while participating in an organized demonstration” (27). A government uninterested in leading right and very invested in maintaining the unjust status quo would seize the opportunity to label a protesting group’s self-defense weapons as a threat to law and order and would then unleash its security forces on the protesters.

We can say much to support the proposition that this generation of Nigerians has mastered the art of protesting. Perhaps even more refreshing, however, is the heightened interest of young Nigerians in the political process following the End SARS protests. I consider this a great and much needed development. The Government has denied generations of Nigerians knowledge of civics through an ineffectual education system. Many of us only learned about the mechanics of government as adults. At no time in all my years of study in Nigeria was I taught Government as a subject, and this is not unique to me. As more and more people become better informed, I believe that we ought to increase our engagement with governments with the goal of taking advantage of our legal systems as they currently are. Yes, the military and singularly North derived 1999 Constitution of Nigeria is replete with many issues. Yet, if we engage that document, with all its imperfections, as I think we ought to do, we can get much improved dividends from it than we currently do. We need to try very hard to stop—and this won’t be easy—the decades-long perfected pessimism

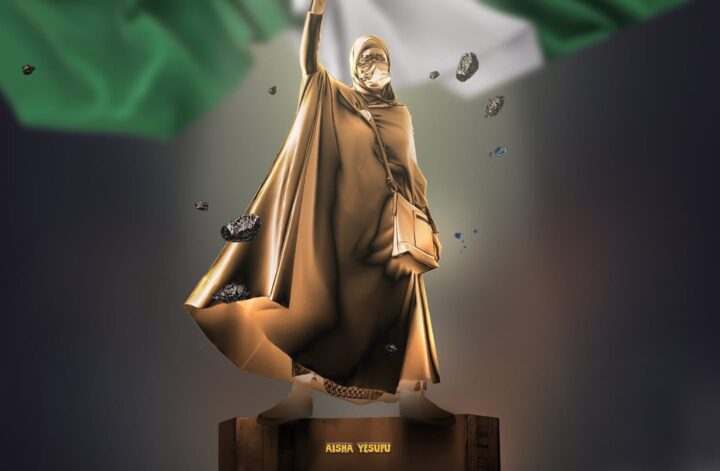

One of the interesting facts of the End Police Brutality (and the SARS) protests in Lagos, Nigeria, was that the on-the-ground-protesters, comprising concerned denizens with no pre-planned organization, had a deep understanding of the logic of peaceful protests and were committed to it. They policed the few among them who did not quite understand the logic. Even more heartening was that they performed free humanitarian services including medical and legal services, raised funds for prosthetics for some protesting members, and distributed cell phone recharge credits. Prior to the protests, I would have been more prepared to believe that Nigerians were too divided and defeated to do anything together. I was wrong! In fact, the protests seemed to have opened up peoples’ creativity as citizens lovingly sought ways to better one another. Some people constructed a massive electrical board for others to charge their phone batteries. The Candle Night memorial gathering in honour of those who the police have murdered may as well be a service in heaven. Perhaps the most surprising of it all was when I learnt that the protesters routinely cleaned up after each day of protesting! I do not know why that piece of information yet makes me immensely proud. Perhaps it is because the Lagosians I remember would have done the very opposite. I still easily recall memories of people dumping their trash cans in the gutter whenever it poured. No-one took thought of her or his neighbour; nobody thought about the local government. Perhaps not all Lagosians littered. Maybe it was a uniquely Agege thing. Whatever the explanation, learning that the protesters cleaned up behind themselves filled me with immense pride.

The point I am making is that the earlier we realize that our political salvation is very unlikely to come from the outside, the sooner we will increase our participation in government. We cannot continue to hope for a messiah to take over the system and change it. This is highly unlikely to ever happen for two reasons. First, as the British politician Lord Acton teaches us, power corrupts. Second, the current Nigerian governmental system is so pro-corruption that it may corrupt even an angel. Nigerian public office holders earn the most in the entire world! This is surely an enormous temptation for anyone. Just consider all the people who have served in government and try to scale their moral weight after they left office: Obasanjo, Tinubu, Osinbajo, Jonathan, El-Rufai, Okonjo-Iweala, Sanusi Lamido Sanusi? The list goes on and the lesson seems to be that the system corrupts people. Hence, given these factors, I now believe that we will fare better protesting and holding office holders accountable while also considering who to field for what office than merely just hoping for a messiah every election year. We need to be consistently informing policies, keep tabs on local politics and state assemblies. We need to become politically sophisticated citizenry–the very thing the system has deliberately denied us for decades. Dr. King further instructs: “We must develop, from strength, a situation in which the government finds it wise and prudent to collaborate with us” (137).

Ultimately, our efforts must have the attainment of political power as the end goal. Now, this power does not even have to be holding a political office—though, this development is definitely part of the goal. The power I have in mind is becoming a formidable force that any government cannot ignore without dire consequences. And to achieve this, we must organize without losing sight of the fact that this may make us easy targets for the government. Perhaps, our organization can be functionally horizontal so that, to use a biblical imagery, there would not be a shepherd to strike that would cause the scattering of the flock. How ever we do it, we must do it to attain power, which can translate our efforts into tangible dividends.

I pray for comfort for the families of those noble soldiers that were felled by the bullets of those who were supposed to protect them. We shall never forget their sacrifice.

Work Cited

King, Martin Luther. Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? Beacon Press, 1967.