Abstract

This entry provides a nuanced examination of 1 Timothy, particularly chapter 2, one of the most contentious texts regarding women in Christian communities. The essay argues that Paul’s instructions to Timothy must be read against the backdrop of the Artemis cult in Ephesus, which had deep cultural, religious, and economic roots in the region and significantly shaped the societal status and expectations of women. Far from enshrining patriarchal norms, Paul’s letter, when read with cultural literacy, reveals a strategy to establish theological clarity and ecclesial stability in a setting deeply influenced by a goddess-centered worldview. Modern readers can better discern Paul’s pastoral intent and theological coherence by understanding Artemis and the Ephesian context.

Earlier in the series, we discussed a unique problem letters pose for understanding. We have looked at letters Paul wrote to the Corinthians and the Ephesians. But the pastoral epistles are different. Whereas the letters to the Corinthians and Ephesians, for instance, were meant to be read aloud to respective church members, the letters to Timothy (and Titus) are personal in a different way because they were addressed to named individuals. Just as it is true for the Corinthian correspondence, we do not know precisely what the problems were because Paul did not spell them out. We also do not comprehensively understand the issues 1 Timothy was written to address. Of course, Timothy and Paul knew what the problems were, but all we have are hints.

Internal Difficulties

1 Timothy 2 is one of the most challenging passages with explicit, seemingly misogynistic words. After all, this is the passage that says women will be saved through childbearing – thereby suggesting that the means or mechanism of salvation differs by gender. Many are Christian women who had too many children because their church traditions taught them that their womb was a highway to heaven. And, of course, considering how dangerous the birthing process still is, many Christian women did lose their lives in childbirth. Many churches treat women differently because of this passage and similar ones today. So, it is a significant passage we will carefully and sensitively address.

To begin with, even a face-value reading of 1 Timothy suggests that more must be going on beneath the surface. Consider the following:

1 Timothy 2:11 NKJV

Let a woman learn in silence with all submission.

Leaving aside the fact that various church traditions have grossly misunderstood the imperative in this verse – focusing on the “silence” instead of the “learn” part – this charge does not square well with what Paul says to the Corinthians:

1 Corinthians 11:5 NRSV

But any woman who prays or prophesies with her head unveiled disgraces her head—it is one and the same thing as having her head shaved.

We have addressed this passage elsewhere. The point here is that Paul takes it for granted that women could pray and prophecy in church settings. This is not surprising because when the Spirit descended on the believers at Pentecost, he did so on both men and women (Acts 1:14, 2:4). Nobody prophecies with her mouth shut. So, the women in the Corinthian church were not silent, and Paul was okay with it. The only relevant problem Paul addressed with the Corinthian church was disorderliness resulting from not taking turns to speak.

Here is another point to consider:

1 Timothy 5:14 NRSV

So I would have younger widows marry, bear children, and manage their households, so as to give the adversary no occasion to revile us.

The first letter to Timothy contains hints implying that the church had a significant problem with single women. In this verse, Paul advises Timothy to encourage young widows to remarry and bear children. This would ensure the church could focus its limited resources on older widows. The problem is that Paul provides the opposite counsel to the Corinthians:

1 Corinthians 7:8-9 NRSV

[8] To the unmarried and the widows I say that it is well for them to remain unmarried as I am. [9] But if they are not practicing self-control, they should marry. For it is better to marry than to be aflame with passion.

Here, Paul encourages the single women in the Corinthian church to remain unmarried, provided they can exercise self-control. He later explains his logic, too: Single people have more time for God than married people do.

There is yet another compounding observation. Paul often spoke well of female colleagues in ministry. Romans 16 lists a bunch of these women with some interesting details, too:

Romans 16:1-3, 6-7, 12-15 NIVUK

[1] I commend to you our sister Phoebe, a deacon of the church in Cenchreae. [2] I ask you to receive her in the Lord in a way worthy of his people and to give her any help she may need from you, for she has been the benefactor of many people, including me. [3] Greet Priscilla and Aquila, my fellow workers in Christ Jesus.

[6] Greet Mary, who worked very hard for you. [7] Greet Andronicus and Junia, my fellow Jews who have been in prison with me. They are outstanding among the apostles, and they were in Christ before I was.

[12] Greet Tryphena and Tryphosa, those women who work hard in the Lord. Greet my dear friend Persis, another woman who has worked very hard in the Lord. [13] Greet Rufus, chosen in the Lord, and his mother, who has been a mother to me, too. [14] Greet Asyncritus, Phlegon, Hermes, Patrobas, Hermas and the other brothers and sisters with them. [15] Greet Philologus, Julia, Nereus and his sister, and Olympas and all the Lord’s people who are with them.

Whatever else Paul was, he did not seem to be a misogynistic narcissist who could not appreciate the gifts and labor of women. Paul here says Phoebe was a deacon and financier of his ministry. This is astounding because various church traditions have used Paul’s letters to Timothy and Titus to argue against women deacons. Yet, the author of those letters mentions a female deacon by name here.

The Priscilla and Aquila of verse 3 are the same couple introduced in Acts 18:1-3. When Apollo, an eloquent, skilled, and knowledgeable believer, came to Corinth to preach Jesus, Priscilla and Aquila perceived that Apollo yet had more to learn. Luke writes:

Acts 18:25-26 NIVUK

[25] He had been instructed in the way of the Lord, and he spoke with great fervour and taught about Jesus accurately, though he knew only the baptism of John. [26] He began to speak boldly in the synagogue. When Priscilla and Aquila heard him, they invited him to their home and explained to him the way of God more adequately.

Now, are we to believe that Priscilla was quiet and in the kitchen all the time Apollo was in her house being instructed about Jesus, even though she was with Paul and learned the way of Jesus? Luke here says “they”—Priscilla and Aquila—explained the way of God more adequately to Apollo. Paul also calls them both his “fellow workers in Christ Jesus.” It is also worth mentioning that Priscilla’s name is often the first listed whenever the couple is mentioned in the New Testament.

Next, in Romans 16, Paul speaks of a certain “Andronicus and Junia.” They very likely were another couple of ministers. Interestingly, Paul says this couple, including the female Junia, “are outstanding among the apostles” and that they were believers in Jesus before he was. So, before the world would divide over Paul’s letters concerning whether women could be pastors and teachers, there already were female apostles in Jesus. Once again, this should not be surprising because when the Spirit descended on Pentecost as Jesus promised, he was no respecter of phalluses. He gifted men and women alike. It makes complete sense that there were women teachers like Priscilla and apostles like Junia. Paul lists other women in Romans 16 who labored hard in the Lord with him.

In Philippians, Paul names two other women:

Philippians 4:2-3 NIVUK

[2] I plead with Euodia and I plead with Syntyche to be of the same mind in the Lord. [3] Yes, and I ask you, my true companion, help these women since they have contended at my side in the cause of the gospel, along with Clement and the rest of my co-workers, whose names are in the book of life.

Euodia and Syntyche were going through a rough patch that is not uncommon in ministry. Paul and Barnabas were in disagreement over whether to have Mark travel with them. Paul says these women “contended at my side in the cause of the gospel.” Again, are we to imagine that the women silently cooked while Paul and the other guys preached the gospel? That is very unlikely.

If Paul preached a phallus-respecting gospel, he would not be preaching the gospel of Jesus. Interestingly, Luke, Paul’s traveling companion, records an occasion when Jesus was in the house of Martha and Mary, Lazarus’ sisters. In this story, Jesus was teaching while Martha understandably was a good host as she cooked for at least thirteen grown male guests. On the other hand, Mary shirked sociocultural norms by sitting at Jesus’s feet to learn from his teaching rather than help in the kitchen. Frustrated, Martha complained to Jesus. Luke reports:

Luke 10:40-42 ESV

[40] But Martha was distracted with much serving. And she went up to him and said, “Lord, do you not care that my sister has left me to serve alone? Tell her then to help me.” [41] But the Lord answered her, “Martha, Martha, you are anxious and troubled about many things, [42] but one thing is necessary. Mary has chosen the good portion, which will not be taken away from her.”

So, Jesus allowed women in his program from the beginning. Judging by the numerous female companions in his ministry, Paul also seemed to have received the memo.

One more point is relevant here. Indeed, the broader culture generally treated women as subordinates. In first-century Palestine, a woman’s testimony was legally inferior to a man’s. Yet, the resurrected Jesus chose to appear exclusively to women, thereby placing them in the position of preaching about what they had seen. In 1 Corinthians 15:13-17, Paul says the resurrection is the cornerstone of the Christian faith. There would be no Christianity had Jesus not risen. Hence, the women who first saw the resurrected Jesus were the first Christian preachers – and they announced the good news of his resurrection to men, including Peter and John. Jesus specifically directed the women to preach what they witnessed to the men (cf. Matthew 28:10, for instance). Now, why would Jesus grant women such a privilege only to take it away from them a few years later? That seems very unlikely. Paul’s words to Timothy are appropriate here:

1 Timothy 6:3-4 ESV

[3] If anyone teaches a different doctrine and does not agree with the sound words of our Lord Jesus Christ and the teaching that accords with godliness, [4] he is puffed up with conceit and understands nothing. He has an unhealthy craving for controversy and for quarrels about words, which produce envy, dissension, slander, evil suspicions

A gospel that maligns women would not agree with the words and deeds of Jesus. So, we have several reasons to suspect that whatever contrary things Paul said to Timothy in his letters were specific to the church under Timothy’s care. They were measures intended to fix particular problems. There is no way to read 1 Timothy 2 at face value, not if we want to believe that Paul was a mentally stable Christian with a love for and knowledge of Jesus.

Locating the Church and the Challenges

So, what is going on then? Thankfully, scholarship has made significant progress on deciphering the first letter to Timothy in very recent years. We still may not be certain about every detail, but we often can be sure about what Paul is not saying in this text. Paul begins this letter with a useful detail:

1 Timothy 1:3 ESV

As I urged you when I was going to Macedonia, remain at Ephesus so that you may charge certain persons not to teach any different doctrine,

Two points are immediately obvious. First, Paul left Timothy behind to combat false teaching. Second, the false teaching in question was happening in Ephesus. So, we know the location of the church(es) under Timothy’s care. This is a very useful bit of information because Luke tells us more about Paul’s missionary trip to Ephesus.

In Acts 19, Paul returned to Ephesus. At first, Paul characteristically entered a synagogue to reason with Jews about the identity of Jesus as the promised Jewish Messiah. He did that for three months (19:8). It soon became clear that some people in the synagogue had chosen against believing and even spoke “evil of the Way before the congregation” (19:9). So, Paul discontinued that enterprise and went to a neighboring “hall of Tyrannus” to reason daily with whoever cared (19:9). He continued this for twenty-four months. Perhaps he persisted for so long because he was so effective, and God blessed the endeavor:

Acts 19:10 ESV

This continued for two years, so that all the residents of Asia heard the word of the Lord, both Jews and Greeks.

Paul was so effective that even members of opposition camps derivatively invoked the name of Paul’s Lord with moderate success. On one occasion, however, seven sons of a Jewish man called Sceva decided to cast devils out of a possessed man in Paul’s Jesus’ name. It was a bad market day for them as the possessed man gave the sons a good beating for invoking the name of a Jesus they did not personally know. The news of this event in Ephesus only further put reverent fear in people’s hearts concerning Paul’s Jesus (19:17). Paul’s ministry was doing well. In fact, Luke reports:

Acts 19:18-20 ESV

[18] Also many of those who were now believers came, confessing and divulging their practices. [19] And a number of those who had practiced magic arts brought their books together and burned them in the sight of all. And they counted the value of them and found it came to fifty thousand pieces of silver. [20] So the word of the Lord continued to increase and prevail mightily.

It is true that Proverbs 10:22 says the blessing of the Lord enriches and that he adds no sorrow to it. But sorrow and troubles are different things. When Paul got in the heads of “all the residents of Asia,” many would inevitably believe and follow Paul’s Lord. Even if they do not follow Jesus, they may hold to their traditional beliefs only loosely. Both scenarios are bad for those who profited from the traditional ways of life. Before long, opposition arose.

Just before the opposition broke out, Paul resolved to visit some of the other churches he had earlier planted, having spent about three uninterrupted years in Ephesus alone. In preparation, he sent some of his assistants to Macedonia while he stayed back in Ephesus. One of these assistants was named Timothy. Judging by 1 Timothy 1:3, Paul must have sent Timothy back to Ephesus later. Paul and his team made multiple trips back and forth among the churches they planted. (See Acts 18:5, for instance.) Notice how this detail implies that Timothy was with Paul in Ephesus from the beginning and, therefore, would have complete knowledge, as Paul, about the challenges of the Ephesian church – the sort of detail neither man would feel compelled to rehash in personal letters.

A silversmith named Demetrius made shrines of the goddess Artemis and became conscious of cash flow. He called an emergency meeting of fellow workmen in similar trades. From him, we got a sense of what Paul preached. Paul had directly undermined Demetrius’ business by preaching that “gods made with hands are not gods” (19:26). That singular move might have helped the Ephesians abandon the goddess of their city. But, as Demetrius sees it, things could get worse:

Acts 19:27-28 ESV

[27] And there is danger not only that this trade of ours may come into disrepute but also that the Temple of the great goddess Artemis may be counted as nothing, and that she may even be deposed from her magnificence, she whom all Asia and the world worship.” [28] When they heard this they were enraged and were crying out, “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!”

The resulting riot was great. So great that Paul left Ephesus for Macedonia.

Demetrius says a few things that are easy for us moderns to miss. The goddess Artemis of the Ephesians, known as Diana to the Romans, was one whom all Asia and the world worshipped. This is not a hyperbole. Artemis had been the goddess of Ephesus at least 500 years before Paul was born. Her renown among the Greek pantheon was second only to Zeus. Indeed, as Sandra Glahn argues in Nobody’s Mother, a proper understanding of Artemis is necessary for clearing up the confusion in Paul’s first letter to Timothy.

Who was Artemis of the Ephesians?

Trigger warning: The following mythological account involves women dying in childbirth.

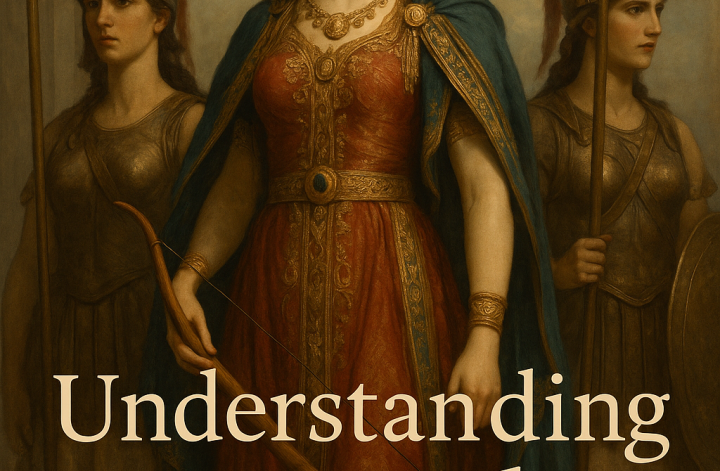

Sandra Glahn marshals epigraphical, Greco-Roman, and patristic literary, archaeological, and Scriptural data to correct some popular ideas in scholarship concerning the identity of Artemis. In Greek mythology, Artemis was the daughter of Zeus and Leto, and the twin sister of Apollo. She was born first and is said to have aided her mother in delivering Apollo, her brother. This is the origin of the widespread belief in Artemis’ role as a protector of women in labor. Leto was said to have labored for nine days before Apollo was born because Hera, another of Zeus’s wives, had kidnapped the goddess of childbirth. Watching her mother in pain for so long made a lasting impression on young Artemis. She went to her father, Zeus, asking to be made a permanent virgin. Artemis was not anti-male; she was only anti-sex. (Glahn, 96). She was a huntress highly skilled in archery. She kills with her deadly arrows anyone who stands in her path. “When humans are involved, her arrows can be painless if death is desired and ruthless if used as an executioner’s tool” (Glahn 115). Though she killed male and female alike, she seemed to have killed women more.

Indeed, as various Greek sources show, Artemis’s role in midwifery was two-fold: she could either bring women safely through childbirth or she would kill them quickly in childbirth to save them from enduring pain for too long before dying. To better appreciate Artemis’ role in midwifery, readers should recall that childbirth was always dangerous, even in our day. In those days in Ephesus, women married at about 14 years, while men were generally older at about 30 when they married. There was no anesthesia, morphine, chloroform, nitrous oxide, or C-section. Every time a woman was pregnant, especially for the first time, she truly was uncertain whether she would survive. Artemis was her only hope – of safe delivery or quick, painless death. Artemis was the traditional savior of Ephesian women.

Among Greco-Roman deities, Artemis of the Ephesians stood as one of the most formidable and widely revered, particularly in Asia Minor. Her Temple at Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, functioned as a religious, civic, and economic powerhouse. This Temple dates to 550 BCE (Glahn, 99). Glahn notes that when this Temple burned down in 356 BC, the year Alexander the Great was born, various kings and dignitaries contributed towards rebuilding it. Some ancient sources claimed the construction took 120 years to complete (Glahn 99). Artemis’ Temple was in the same league as the Great Pyramid of Giza. So, Demetrius and the other workers in Acts 19 faced an actual economic loss with Paul’s gospel. Besides, Artemis was also known by numerous titles and epithets that reflected her vast jurisdiction. Some of these descriptions are particularly relevant. Theoi Project, an online resource, lists tens of titles for Artemis, including Locheia (protector in childbirth), Parthenos (Virgin), Phosphoros (“Bringer of Light”), and Kourotróphos (nurturer of children), Soteira (“The saving god”), Protothronia (“of the First Throne”). Based on what we know of Paul, there was no way he would allow some of these titles to stand unchallenged if he could do something about it.

Another important relevant detail concerns how Artemis Ephesia dressed. She is often portrayed in sculptures in heavily embroidered, opulent, and ceremonial dresses that mark her as a cosmic queen. “Artemis is the lord of virginity, who wears a gold belt, drives a golden chariot, and sits on a golden throne” (Glahn, 55). Artemis’ devotees near Ephesus routinely took expensive dresses to her shrine as an act of worshipful devotion. Glahn notes a legal case in 4 BC involving a death sentence for forty-five people who assaulted “a sacred delegation dispatched from Ephesus to the shrine of Artemis in Sardis with tunics for the goddess” (131). Those tunics were so valuable that forty-five people risked their lives. This practice had significant cultural implications in Ephesus, where women took pride in dress as a form of religious identity. Indeed, “when the average Roman woman in antiquity stepped outside her home, her apparel and hairstyle would have conveyed visual signals about her rank (citizen, freeborn, slave), her marital status, in some cases her age, and even her moral status” (Glahn 132). As we shall see shortly, Paul has much to tell Timothy about Ephesian women’s dress and coiffure.

One final point connected to Artemis is worth noting. In Greek mythology, the Amazons were elite virgin female warriors and daughters of the god of war, Ares. They were typically depicted wearing short, belted tunics, one-breasted armor, and sometimes loose pants. The Amazons are said to be the founders of Ephesus. Artemis was their patron deity, and she was worshipped as the city’s protector (Glahn 116). Hence, this Amazonian imagery intersected with the cult of Artemis, likely influencing how female devotees dressed and presented themselves, especially priestesses who were usually virgins while serving. Their attire signaled devotion, independence, and power, making clothing a socio-political and cultural statement.

Considering what life looked like centuries before Paul took the gospel to Ephesus, we can understand the problems that might result when Ephesians converted to Jesus en masse. They, like all of us, had much mind renewal to undergo. In the early days, we can expect a good measure of syncretism as people learned to let go of their earlier beliefs and swapped worldviews. Armed with this information, we are now ready to explore 1 Timothy.

1 Timothy 1—2: What Can We Discern?

We have already learned that a major problem in the Ephesian church was false teaching, resulting in inappropriate behaviors and manners in the church. Certain unnamed persons were teaching different doctrines, devoting “themselves to myths and endless genealogies, which promote speculations rather than the stewardship from God that is by faith” (1:4). Considering that Paul says these teachers were eager to teach the Torah without having a clue about what they so confidently asserted (1:7), it is plausible that these teachers were Gentile Ephesians – probably men and especially women. Jews are unlikely to be described as not “understanding either what they are saying or the things about which they make confident assertions” (1:7) concerning the Torah. Whoever they were, Paul wanted them to stop propagating falsehood out of “love that issues from a pure heart and a good conscience and a sincere faith” (1:5).

Paul proceeds to discuss the purpose of the Torah as being for the lawless and the disobedient, not the righteous (1:10). He also quickly recaps his former life as a blasphemer and persecutor of the church of Jesus, ending with the following:

1 Timothy 1:16 ESV

[16] But I received mercy for this reason, that in me, as the foremost, Jesus Christ might display his perfect patience as an example to those who were to believe in him for eternal life.

Since Timothy very likely already knew Paul’s conversion story, having been his ministry companion for years, his narration here as the “foremost sinner” (1:15) whom Jesus saved may reveal his heart posture towards the church problems he is about to address. Paul says Jesus showed “his perfect patience” as an example for others, including even the false teachers in this troubled Ephesian church. Paul might have intended this to reiterate his comment about a “love that issues from a pure heart and a good conscience and a sincere faith” (1:5). He mentions two people, “Hymenaeus and Alexander, whom I have handed over to Satan that they may learn not to blaspheme” (1:20). Being a former blasphemer himself (1:13), Paul likely temporarily expelled these fellows from the church to teach them a lesson. If they repent, Paul very likely will accept them as he did with the fornicating Corinthian, whom he also handed over to Satan (see 1 Corinthians 5:5 and 2 Corinthians 2:5-11).

Paul continues to address the Ephesian church problem in chapter 2. He begins thus:

1 Timothy 2:1-2 NIVUK

[1] I urge, then, first of all, that petitions, prayers, intercession and thanksgiving be made for all people – [2] for kings and all those in authority, that we may live peaceful and quiet lives in all godliness and holiness.

Verse 1 is a recognizable Pauline ministry method. Paul believes that general peace in a land is good for the gospel message. He urges prayers for people in the government because they have much to do with whether believers can “live peaceful and quiet lives” (2:2). One bad government policy can significantly alter the landscape for believers. Paul further assures Timothy that saying such prayers for government officials is good:

1 Timothy 2:3-5 NRSV

[3] This is right and is acceptable in the sight of God our Savior, [4] who desires everyone to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth. [5] For there is one God; there is also one mediator between God and humankind, Christ Jesus, himself human

Scholars have postulated a possible polemic against Artemis in these verses. The words “God” (theo), “Savior” (soter), and “saved” are all traditionally associated with Artemis in Ephesus. She was the Ephesians’ goddess, city protector, and savior. Paul’s additional comment that there is one God and one mediator between God and humans ensures that no room is left for Artemis in the cosmos. She cannot help anyone because she is neither the only true God nor the appointed mediator. Glahn notes a contrast between Artemis and the mediator between God and humans, “Instead of remaining only on the receiving end of sacrifices, which would be his right, he ‘gave himself as a ransom for all, revealing God’s purposes at his appointed time'” (129). Paul continues:

1 Timothy 2:8-10 NRSV

[8] I desire, then, that in every place the men should pray, lifting up holy hands without anger or argument; [9] also that the women should dress themselves modestly and decently in suitable clothing, not with their hair braided, or with gold, pearls, or expensive clothes, [10] but with good works, as is proper for women who profess reverence for God.

Apparently, this church was so dysfunctional that the men were angrily quarreling with some church members, very likely the women, during prayer. This reading is plausible because Paul immediately shifts from the men to addressing a woman’s problem in the church. It is worth reminding readers that Koine Greek, the ancient language Paul wrote in, had one word for both “wife” and “woman.” It also had one word for “husband” and “man.” So, scholars use context to determine the appropriate translation. Often, we cannot be certain. In 1 Timothy 2, “woman/women” could be translated as “wife/wives.” The same is true for man/husband.

Older Western exegetes misunderstood Paul’s instruction to the women here. They thought there was a sexual undertone where none existed. The women did not dress provocatively. On the contrary, they were classy and flaunted opulence. This sartorial standard was appropriate for the devotees of Artemis. It could be that this expensive presentation in church meetings provoked anger and quarreling among men. Since Paul firmly believes that the ethics and rules of conduct in Jesus are different and inclusive, he wants women to be considerate. No point showing up to church with all the diamonds (which pearls were to first-century women) and gold. It would be better and sufficient to clothe oneself with appropriate good works for fellow humans. In other words, instead of appearing in a way that might ruin someone else’s day, Paul wants the women to work for the wellbeing of that other person. That is Jesus’s way of living – a way in sharp contrast to Artemis’.

We are now ready for the hotly contested verses in the passage:

1 Timothy 2:11, 12 NIVUK

[11] A woman should learn in quietness and full submission. [12] I do not permit a woman to teach or to assume authority over a man; she must be quiet.

Various Christian traditions have misplaced the imperative in verses 11 and 12. Paul’s emphasis was not that an Ephesian woman should be quiet but that she should learn in quietness. This “quiet” language is the same root word Paul applied to the whole church, male and female, in verse 2, about living peaceful and quiet lives.

But why might Paul have thought this was a good idea? Earlier in the letter, Paul said “certain persons” were teaching false doctrines. As we have seen, women in Ephesus played leading roles in their society – including as priestesses of the cult of Artemis. Even if an Ephesian woman did not play any of these traditional roles, it is not difficult to see how that culture would have been shaped so that women had more power or, in any case, played more active roles in that society. Hence, it could be that the women were also leading in this church but ineffectively. Paul said earlier that certain people desperately wanted to teach the Torah, the basis of the Christian faith, but made a mess of it. It is not unlikely that the teachers Paul had in mind were the women or, perhaps, a majority of the women.

There is another plausible explanation. We have already noted that Paul seemed to appreciate the value of political stability for spreading the gospel message (1 Timothy 2:1-2). Rome had laws forbidding women from intervening between two parties in public settings. Quoting another scholar, Glahn notes, “an imperial ban already existed from the time of Augustus on women intervening on behalf of their husbands in the context of legal argument” (135). Recall that a church in the first century was typically a gathering in someone’s house that would have other couples in attendance; it is not difficult to see why Paul would want to stop the problem of making men (or husbands) quarrel angrily during prayers in the church. He could be mindful of the civil laws while trying to teach the Ephesians how to “behave in the household of God, which is the church of the living God, a pillar and buttress of the truth” (1 Timothy 3:15).

Verse 12 is difficult to exegete because it contains a hapax legomenon, a word that only occurs once in a corpus or the entire Bible. In the business of translation, scholars often study how a term is used in various places to determine the best meaning of the word. The word translated here as “assume authority over” (“authentein”) only occurs here in the whole Bible. Predictably, opinions are diverse on how to understand it. Some scholars think verse 12 contains two commands: a woman (or wife) may not teach, and a woman (or wife) may not exercise authority over a man. In this reading, Paul would be giving different but related instructions. It is also possible to read the verse as containing one instruction: a woman (or wife) may not teach a man (or husband) because that would amount to exercising authority over a man – which is somehow not right. These readings, at face value, seem supported by the following two verses:

1 Timothy 2:13-14 NIVUK

[13] For Adam was formed first, then Eve. [14] And Adam was not the one deceived; it was the woman who was deceived and became a sinner.

So, as a basis for his instruction that the Ephesian women should learn in quietness and not be teachers, Paul alludes to the creation story, saying Adam was formed first. There is something about the ontological priority of Adam that makes it wrong for a woman to teach or “exercise authority over a man,” whatever that means. Paul quickly follows this explanation with, “Adam was not the one deceived; it was the woman who was deceived and became a sinner.” If this reading is correct, it would follow that this ruling applies to all women, not just the Ephesian women.

But is it correct? First, there is evidence that “authentein” refers to usurping authority, as the KJV translates it. If this alternative reading is accurate, it suggests that the women (or wives) acted this way in response to the men. Glahn writes (139):

the author’s instruction suggests that both husbands and wives in the assembly need to calm down. The men/husbands are angry during prayer, and the women/wives are acting in a way that communicates a sense of superiority or perhaps violates civil law.

Glahn also offers an alternative translation of verse 12: “I am not permitting a wife to teach with a view to domineering a husband, but to be in quietness” (Emphasis original to the quote, 139).

Besides, as we have learned in our exploration of similar ideas in 1 Corinthians, the ideas in verses 13 and 14 seem questionable enough for us to wonder if there might be a case of Paul quoting the Ephesians or something similar. First, the statement that Adam was formed deserves a comment in light of what we argued elsewhere. There is only one sense in which the male human of Genesis was formed first. The human God created and placed in the Garden was not described in gendered terms until Genesis 2:22 – 23. Adam was formed first precisely when God put the human to sleep and took a piece out of his side to form the woman. That time interval is the moment the gendered male human came to be, not prior. Now, this does not imply subordination. The woman is not inferior in any way to the man. On the contrary, the man and the woman are different expressions of interdependent equality. (See our treatment of Genesis 2 here.)

The idea that it was the woman who was deceived and became a sinner is very problematic because that is emphatically an inaccurate and incomplete story. In the Genesis account, Adam was right there next to Eve while she was being deceived (Genesis 3:6). When Eve offered him of the fruit of the forbidden tree, Adam did not protest or otherwise tried to carry out God’s instruction. So, if Adam was not deceived, he surely did not act like it. Moreover, Eve was not the only one who became a sinner. Both she and Adam became sinners, and Paul acknowledges this point in other letters:

1 Corinthians 15:22 NIVUK

For as in Adam all die, so in Christ all will be made alive.

Notice Paul does not say, “in Eve all die.” Here is another reference:

Romans 5:12, 14 NIVUK

[12] Therefore, just as sin entered the world through one man, and death through sin, and in this way death came to all people, because all sinned –

[14] Nevertheless, death reigned from the time of Adam to the time of Moses, even over those who did not sin by breaking a command, as did Adam, who is a pattern of the one to come.

Again, Paul says sin entered the world through one man, not a woman. He furthers says Adam broke a command without even mentioning Eve. So, 1 Timothy 2:13-14 is unlikely to be Pauline in origin – unless we want to posit that Paul was mentally unstable or incompetently inconsistent.

The question remains: so what roles do these verses play in the argument of the letter? Opinions differ. One plausible account says Paul might have felt the need to stress the creational priority of man because the Ephesian women were doing the opposite. Remember that in the mythological birth story, Artemis was born first before her brother, Apollo. So, the Ephesians inherited a mythic-historical narrative of the priority of the woman.

Furthermore, as already mentioned, the Ephesian culture was probably matriarchic in some significant ways. Since these women wanted to be teachers of the Torah so desperately, these verses may indirectly tell us just how badly the Ephesian women teachers mishandled the text and faith. They could not even correctly understand that Adam was first. If this theory is correct, we would be right to suspect some syncretism going on in that church. No wonder Paul wanted them to teach no more but learn in quietness!

We have finally come to the most vexing verse in this letter:

1 Timothy 2:15 ESV

Yet [woman] will be saved through childbearing—if they continue in faith and love and holiness, with self-control.

Some translations like the NIV conceal a grammar problem in this verse. Notice that “woman” is singular, but “they” is plural. Since the verse comes on the heels of 13 and 14, it could also contain an Ephesian quote. Glahn observes (146-147): “part of this statement could be quoted material: “and ‘she will be saved in childbearing.'” Then he tacks on the qualifications (“if”) and then ends with the phrase, “This is a faithful saying.” Her reading is far more plausible.

As we saw earlier when addressing related issues in 1 Corinthians, Paul often use local sayings in his corresponces – sayings the original recipients would have unmistakably understood. Glahn includes a detail in the quote above that is worth stressing. Whereas many English translations have often appended πιστός ό λόγος, sometimes translated as “This is a faithful saying” to 1 Timothy 3:1, thereby implying that the “faithful saying” is about a desire to be a deacon, Glahn convincingly argues that this clause fits better with the prior verse about childbearing.

What is this verse talking about? There have been church traditions that teach that a woman will be saved through motherhood, thereby suggesting that a woman’s womb can play a role in her eternal salvation. There is simply no way this could be true at face value. The salvation of women is not dependent on the fruitfulness of their wombs. The questions are endless – what about barren women? Or women who became barren because of trauma? Or women who do not desire to be mothers? Or women who would want to be mothers but died for Jesus before they could be mums? This idea is simply a false gospel, and we can rule it out.

A more plausible explanation is to see Artemis behind the verse. Traditionally and for centuries, Artemis was the Ephesian women’s savior (“soter”) through the precarious act of childbirth. She was the goddess of midwifery, believed to be capable of making childbirth painless and successful. It is not unlikely that some Ephesian Christian women continued to hope in Artemis during pregnancy. 1 Timothy 2:15 may be Paul’s way of assuring women that Jesus, not Artemis, is the one who can grant safe childbirth. The argument for this has two parts. First, Paul opens this letter by applying Artemis’ epithets to Jesus:

1 Timothy 1:1 ESV

Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by command of God our Savior and of Christ Jesus our hope,

Paul says here that another God, not the goddess Artemis, is the Soter and that Jesus, not Artemis, is the hope of Christians, especially pregnant women. The second part of the argument is embedded in the 1 Timothy 2:15 text itself:

1 Timothy 2:15 ESV

Yet [woman] will be saved through childbearing—if they continue in faith and love and holiness, with self-control.

Notice how Paul qualifies “saved through childbearing” with the following: “if they continue in faith and love and holiness, with self-control” – attributes that mark a Christian. In other words, Paul says the women will be saved through childbearing if they remain Christians – not reverting to a devotion to Artemis – and place their hope and trust in the true Soter, not Artemis. This should probably not be taken as a promise that all Ephesian pregnancies will be safe. I think Paul’s larger point is that Artemis is not the real deal. He accentuates this point with “this is a trustworthy saying.”

Reading Paul’s letter to Timothy without considering Artemis’s pervasive influence in Ephesus is to miss the cultural subtext of many of his arguments and allusions. Far from writing abstract theology, Paul practically engages the dominant religious ideology of the region—one that upheld a virgin goddess who protected women in childbirth, symbolized female spiritual autonomy, and was intertwined with myths of female power and priority. Paul’s responses in 1 Timothy, especially regarding childbearing and modesty, subtly but deliberately reframe spiritual authority around Christ and away from Artemis’s domain. His instruction that Ephesian women should stop teaching was a practical step to solve a pressing problem. Once the problem resolved, Paul would have allowed competent and gifted women to teach. Understanding Artemis, then, is key to understanding Paul’s rhetorical strategy in one of the most theologically contested letters in the New Testament.

Works Cited

“Cult of Artemis: Titles” Theoi Greek Mythology, edited by Aaron J. Atsma, Theoi Project, www.theoi.com/Cult/ArtemisTitles.html. Accessed 26 May 2025.

Glahn, L. Sandra. Nobody’s Mother: Artemis of the Ephesians in Antiquity and the New Testament. IVP Academic, 2023.