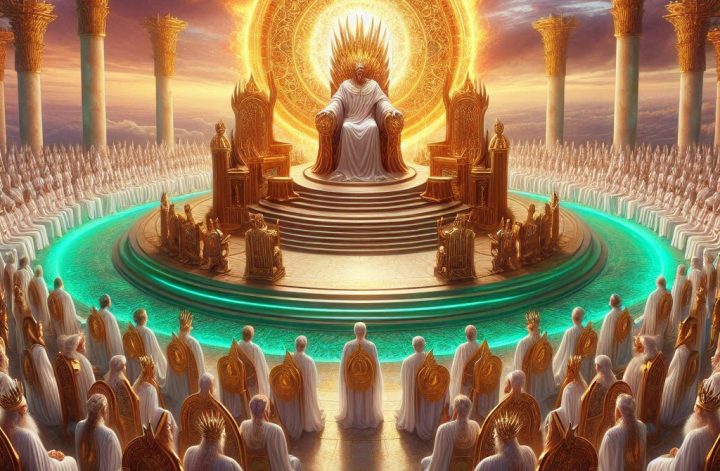

With a joking undertone, I wrote earlier that had John written the book of Revelation as a graduate school work in today’s world, he would score an “F” for plagiarism – failure to cite his sources. I was not exaggerating. In Part 1, I demonstrated how John uses the finest textual details to make theological points. In Part 2, we considered the human and angelic identity arguments of the angels of the seven churches in Revelation. Something similar is going on with our present subject of the identity of the twenty-four elders. Are they human or divine beings? As it turns out, John provides enough data to argue both ways. John uses many different Hebrew Bible imagery, allusion, and ideas in describing the elders in Revelation.

I recently had a Facebook discussion with a Catholic priest, Chinaka Justin Mbaeri, on this subject. He uses his page to educate readers on the heritage and doctrines of the Catholic Church while also correcting what he believes are dangerous ideas to the faith. In one such post, the priest argues at a considerable length in defence of the Catholic Church’s uses of images and statues in its affairs. He argued that Protestants of Nigerian extractions are ill-informed about the practice and so condemn what they know not. He pointed out that Catholics do not worship images or statues but use them as visual aids to teach members of the faithful exploits of saints. He vigorously defends these uses, pointing out that the Bible doesn’t condemn the use of images per se but strongly prohibits worshiping images – and I think he is right. He then says that when Catholics seek the prayer of saints, they are under no delusion that the saints (or their statues) have any power to grant prayers. On the contrary, the idea is to enlist the saints, who are already perfected and in God’s presence, to pray alongside the earthly faithful. He relies on Revelation 5:8 and 8:3-4 as the critical passages for the practice, which is where I disagree. Let me quote these verses below for easy reference before sharing the unedited exchanges: