The Easter Story Retold: How It All Started

According to the Christian calendar, the Holy Week commemorates the most important week ever in the cosmos’ billion years of existence. It is the week of Easter or, to be more inclusive, the week leading to Resurrection Sunday. The idea that one week can identifiably be more significant than all others may offend a thinking mind at first. After all, we have repeatedly heard the argument that our earth is only a speck in the big picture of things. It is an argument asserting that size matters. Ordinarily, I would agree with the argument, but there are exceptions. People do not usually conclude, for instance, that the butt is more important than the brain due to size. Similarly, a speck of uranium may be considered more important than the mountain of trash standing over it.

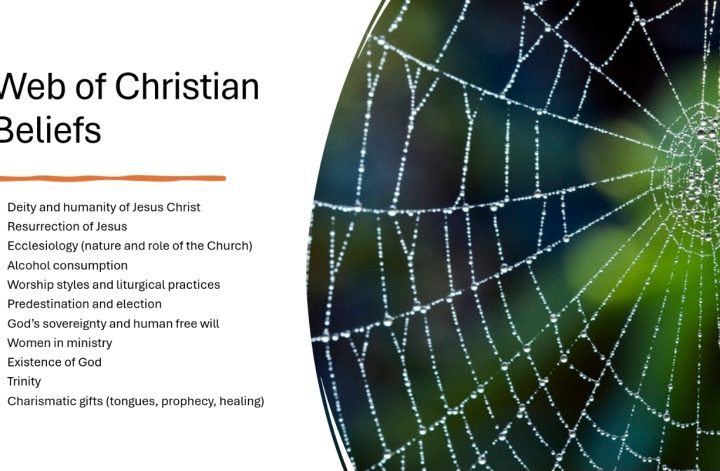

For generations, churchgoers have been taught to believe that a Messiah became necessary because of Adam and Eve’s sin, but that is an incomplete story that accounts for only one-third of the data. To be sure, the story arc resulting in the Messiah’s coming began with Adam and Eve, but there is more. Let us begin from the beginning.

So, how did we get here? As far as we can tell, an uncreated creative mind wanted to get to work. Evidently, it was not his first attempt at creating. He had already created a myriad of essentially immaterial beings “eons” prior to the “moment” he decided on another project. Undoubtedly, there were innumerably infinite ways the project could have taken shape. But just as he had to narrow down the options with his other creative projects, he must do the same here. God decided to make a class of beings constructed of molecules for unrevealed reasons – a terrifyingly complicated undertaking.

How do you build a being from molecules? Easy — you start with, well, molecules! The problem is that molecules did not exist yet. So, the ultimate project must wait as God began by creating the Carbon, Hydrogen, Oxygen, Phosphorus, Sulphur, and other isotopes needed to make the molecules from which his end product would be constructed. But how long would the construction project have to wait? It is not very long – only about 30 million years, which apparently equals about a few days in God’s reference scale. Once the material universe was in place with its arrays of stars coming into and out of existence and all the requisite atoms were available, God could initiate the building of functional molecules.

It soon became clear that God did not want wild humans. Hence, though he had caused vegetation to spring up everywhere on the blue globe, he yet proceeded to carve out a garden for the creature he was about to construct. The human was going to be cultured. After arrangements for human flourishing were in place, God finally built his project after waiting a few million years, a dating that excludes moments “before” the cosmos came to be. The human God created was neither male nor female. It was a genderless composite. In time, it became apparent that the human would not optimally flourish in its composite state. It must be split equally into two complementary forms. Hence, God formed the woman from a rib of the human he had made. It is interesting to note that the Hebrew term for “rib” is a construction term often used to describe a side of a temple. Here, then, is how we finally got the gendered male and female humans. She was in no way inferior to the man. Yes, she was a suitable “help” for the man, but “help” often describes how God is a “help” to humans. If “help” suggests any asymmetry, it is probably in the other direction.

I wish they lived happily ever after, but there would not be a worthwhile story if they did. Some of God’s earlier creations were not down with God’s new hairy creatures. It is not immediately clear if it is the hair or something else, but those older immaterial beings were ticked. Soon enough, they figured out how to mess up God’s project. They would corrupt the young creatures before they have exercised their spiritual muscles unto maturity. Obviously, this implies that the hairy creatures were not incorruptible. If they became corrupted, it was because they could be corrupted. They were not perfect, only good. Very good, actually. Sinister forces succeeded and corrupted the humans.

What was God to do? Another 30 million years is nothing to an eternal being, but starting afresh would communicate lasting victory to the sinister forces. He must find a way to undo the damage. However, we soon learn that God is not in a hurry. Just as he took his time to execute the creation project, he seemed just as relaxed in his redemption plans. It will take a few thousand years to sort things out. In the meantime, however, things became terrible very quickly.

Bashan and Genesis 6’s Sons of God

By the second generation, while there were only four named humans in the story, a man would remorselessly murder his own brother. But that was only the beginning of moral decay. The corruption would soon become supernaturally charged. In Genesis 6, we read the following:

Genesis 6:1-4 ESV

[1] When man began to multiply on the face of the land and daughters were born to them, [2] the sons of God saw that the daughters of man were attractive. And they took as their wives any they chose. [3] Then the Lord said, “My Spirit shall not abide in man forever, for he is flesh: his days shall be 120 years.” [4] The Nephilim were on the earth in those days, and also afterward, when the sons of God came in to the daughters of man and they bore children to them. These were the mighty men who were of old, the men of renown.

This is a hotly debated pericope; we shall not attempt to settle it here. It is fair to say that the standard view in our churches today is that the “sons of God” are humans – whether human kings, descendants of Seth, or something similar. I shall only point out to readers that this reading is a more recent (4th century AD) position. A much older Second-Temple Era tradition takes the “sons of God” as supernatural beings/angels, and the evidence for this reading, in my view, is much stronger. Besides, as we shall see, the angelic interpretation has immense explanatory power. The Genesis 6 passage builds on the earlier chapter. Genesis 5 is a genealogy featuring extraordinarily long life spans. Adam, for instance, lived for 930 years, and Methuselah famously lived for 969 years. Scholarly debates continue as to whether these are literary or literal ages. However, our pericope in Genesis 6 suggests that the human life span was cut shorter to 120 years. Exactitude does not seem to be the point because people lived longer than 120 years afterward but significantly less than the ages reported in Genesis 5.

If we suppose the “sons of God” are supernatural beings, then Genesis 6:4 would suggest that the Nephilim were the offspring of the sexual union of angels and women. These Nephilim are often identified as giants who descended from Anak (Numbers 13:33). They are, hence, also called Anakim (or Anakites) and lived in the land Israel was to inherit, Canaan (Joshua 11:21, 22). Though it remains an offensive and troubling issue in popular discourse, one of the literary reasons God would have the Israelites wipe off everyone in Canaan was because they were descendants of the Nephilim. The famous Goliath was also of the Nephilim. In other words, God was somehow using the Israelites to solve an ancient problem of angelic corruption in his project.

Some well-known non-canonical Second-Temple era Jewish literature unequivocally understood the “sons of God” as defiant angelic beings (1 Enoch 6 and Jubilees 5, for example). We may also have a New Testament witness to this tradition of reading Genesis 6. Consider the following:

2 Peter 2:4-6

[4] For if God did not spare angels when they sinned, but cast them into hell and committed them to chains of gloomy darkness to be kept until the judgment; [5] if he did not spare the ancient world, but preserved Noah, a herald of righteousness, with seven others, when he brought a flood upon the world of the ungodly; [6] if by turning the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah to ashes he condemned them to extinction, making them an example of what is going to happen to the ungodly;

This passage speaks of “angels when they sinned” (verse 4). When was that? It does not explicitly say but moves on to the time of Noah. The careful reader would immediately notice that the story of Noah and the flood is in the same chapter that discusses how the “sons of God” copulated with women. It is, therefore, very plausible that Peter here says God consigned those sinning “sons of God” to hell and that he “did not spare the ancient world” precisely because he wanted to wipe off the Nephilim from the earth, a project that continued even through the ancient Israelites, as earlier mentioned en passant. Besides, the 2 Peter passage also referenced Sodom and Gomorrah, ancient cities known, among other things, for their terrorizing and inappropriate sexual practices. Peter could have cited the sexual practices of these cities as a contrast with the order-defying sexual practice of the “sons of God” of Genesis 6. Indeed, the passage talks about “those who indulge in the lust of defiling passion and despise authority” (2 Peter 2:10 ESV). Of course, the acts of angels copulating with women are an exercise in “defiling passion,” which also despises the authority of God and his established order of reproduction according to kinds (Genesis 1:11).

In the non-canonical Second-Temple era work called 1 Enoch, the “sons of God” entry point onto the earth is believed to be Mount Hermon (1 Enoch 6:1-6), also called Mount Sirion and Senir (Deuteronomy 3:9). It was the tallest mountain in ancient Israel serving as the northern border of Bashan, east of the Sea of Galilee. In the days of Joshua, after the Israelites had conquered the land, Bashan was allotted to the half-tribe of Manasseh:

Joshua 13:30 ESV

Their region extended from Mahanaim, through all Bashan, the whole kingdom of Og king of Bashan, and all the towns of Jair, which are in Bashan, sixty cities,

This Og king of Bashan came at the Israelites while they were coming out of the wilderness to battle with them:

Deuteronomy 3:1-2 ESV

[1] “Then we turned and went up the way to Bashan. And Og the king of Bashan came out against us, he and all his people, to battle at Edrei. [2] But the Lord said to me, ‘Do not fear him, for I have given him and all his people and his land into your hand. And you shall do to him as you did to Sihon the king of the Amorites, who lived at Heshbon.’

The implication is that Og and his people are descendants of the Nephilim.

Furthermore, Psalm 68 also has a lot to say about Bashan. Consider the following selected verses:

Psalm 68:1, 15-16, 18, 20 ESV

[1] God shall arise, his enemies shall be scattered; and those who hate him shall flee before him!

[15] O mountain of God, mountain of Bashan; O many-peaked mountain, mountain of Bashan! [16] Why do you look with hatred, O many-peaked mountain, at the mount that God desired for his abode, yes, where the Lord will dwell forever? [18] You ascended on high, leading a host of captives in your train and receiving gifts among men, even among the rebellious, that the Lord God may dwell there.

[20] Our God is a God of salvation, and to God, the Lord, belong deliverances from death.

The Psalm unequivocally begins with an expectation that Yahweh will arise to battle with his enemies. These enemies are identified as relating to Bashan. Indeed, the Psalm says Bashan is envious of Zion, the mountain God desires as his forever residence. (Note that the ancients believed that gods lived in mountains, regions of the earth that were removed from ordinary human incursions.) Next, we get the familiar verse that Paul applies to Jesus in his letter to the Ephesians: “You ascended on high, leading a host of captives in your train and receiving gifts among men, even among the rebellious, that the Lord God may dwell there.” Finally and critically, the Psalm links this divine battle with Bashan to human salvation from death. As pointed out later, this is directly connected with “the gates of Hades” of Matthew 16.

Interestingly, by applying the Psalm to Jesus, Paul affirms that Jesus fulfills the expectations of this Psalm. The Psalm promises a deliverance from death, a central component of the Gospel that Paul preached. Two additional points are worth making here. First, this is yet another example of the subtle ways New Testament authors affirm that Jesus is Yahweh. Undoubtedly, the God that Psalm 68 expects to battle with Bashan is the Yahweh of Israel. Yet, the monotheistic Jew, Paul, has no problems placing Jesus in that spot of Yahweh. Also, Paul’s use of the Psalm implies that the functioning of the ministry gifts Jesus gave the church somehow contributes to deliverance from death, even as they equip saints for ministry work. We shall have more to say shortly.

The Role of Noah

We began the story from the beginning of humanity’s slide into decay. With only four named persons, there was a murder. We also saw supernatural beings’ role in increasing corruption in the land when angelic beings took on flesh and birthed the Nephilim of old. By the middle of Genesis 6, here is the report of that world:

Genesis 6:12-13 ESV

[12] And God saw the earth, and behold, it was corrupt, for all flesh had corrupted their way on the earth. [13] And God said to Noah, “I have determined to make an end of all flesh, for the earth is filled with violence through them. Behold, I will destroy them with the earth.

So, the corruption and violence only increased, and God concluded that the generation had to be wiped out. But Noah and his family were rescued. It is vital to remember that the people rescued were part of a corrupt generation. The text does not tell us how Noah found divine favor, but we read that Noah obeyed and performed the tasks given to him (Genesis 6:8, 22). And everyone who believed Noah was also rescued. After the flood wiped out life on the earth, we read:

Genesis 9:1-3 ESV

[1] And God blessed Noah and his sons and said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth. [2] The fear of you and the dread of you shall be upon every beast of the earth and upon every bird of the heavens, upon everything that creeps on the ground and all the fish of the sea. Into your hand they are delivered. [3] Every moving thing that lives shall be food for you. And as I gave you the green plants, I give you everything.

The careful reader ought to catch the allusions embedded in this passage. Earlier, God said, “Be fruitful and multiply” to the humans in the Garden of Eden. The language of dominion over the animals is also reminiscent of the task given to Adam. Even Genesis 9:20, “Noah began to be a man of the soil, and he planted a vineyard,” is a clear allusion to Genesis 2:15, “The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to work it and keep it.” There are thus two literary functions performed by the Genesis 9:1-3 verses above. First, the world must be repopulated with Noah and his people just as Adam and Eve had to do, being the first humans (Genesis 9:19). But there is more. The verses above also remind the reader that God had not given up on addressing the problems caused by Adam and Eve. Indeed, the flood became necessary because what Adam initiated had degenerated into worse acts of violence and evil.

However, the flood was no real solution; it only slowed the decay but did not reach the root. Indeed, one of Noah’s sons would soon remind us that the problem remains. After Noah had resettled post-flood, he drank from the wine of the vineyard he had planted. He became drunk and fell asleep naked. Next, we read:

Genesis 9:22-25 ESV

[22] And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father and told his two brothers outside. [23] Then Shem and Japheth took a garment, laid it on both their shoulders, and walked backward and covered the nakedness of their father. Their faces were turned backward, and they did not see their father’s nakedness. [24] When Noah awoke from his wine and knew what his youngest son had done to him, [25] he said, “Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be to his brothers.”

This is a problematic passage for a few reasons. Though the passage’s text merely says Ham saw his daddy’s nakedness, verse 24 says Ham did something to his daddy while he was asleep. Merely seeing someone’s nakedness does not equal “doing” something to them. Besides, it likely was not Ham’s first time seeing his dad naked, especially when he was a little boy. The other problem is that Noah cursed not Ham, the perpetrator, but Ham’s son, Canaan. These observations have generated many interesting conversations concerning the nature of Ham’s offense, including voyeurism, paternal rape, or incestuous sex with Noah’s wife (and Ham’s mother). Now is not the time to flesh out the arguments. Regardless of how we read the story, it is a reminder that this son of Noah was no different from the others killed in the flood. In other words, again, the flood did not solve the problem of evil inclinations in human hearts. It merely scaled it down.

Shortly afterward, we are introduced to the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11) following a Table of Nations (Genesis 10). The world was being repopulated again through the three sons of Noah after everyone else died in the flood. As if to remind us that the flood did not solve a problem, the new generation of humans yet decided against God’s directive by choosing to congregate in a chosen spot rather than spread far and wide:

Genesis 11:4 ESV

Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves, lest we be dispersed over the face of the whole earth.”

So, they explicitly intended not to be “dispersed over the face of the whole earth” – the very result God wanted all along from the days of Adam. With a measure of irony, though they were going to build a tall tower reaching to the sphere of the gods, the Most High God came down instead to inspect the defiant project (Genesis 11:5). Twice, in consecutive verses, the passage says God ensured that the people were eventually dispersed over the face of earth as God always wanted (11:8,9). God achieved this desire by confusing the people’s language.

Abraham is a Major Character

Ten generations and 465 literary years later, God made a pivotal move toward solving the problems we have been discussing. Perhaps God waited until the genetic contributions of the “sons of God” and Nephilim in the gene pool were washed out. Whatever his reasons, God decided to call a 75-year-old childless Abram to derive an ultimate son from his lineage. Nine generations after Noah, God made a move:

Genesis 11:31 ESV

Terah took Abram his son and Lot the son of Haran, his grandson, and Sarai his daughter-in-law, his son Abram’s wife, and they went forth together from Ur of the Chaldeans to go into the land of Canaan, but when they came to Haran, they settled there.

So, Abram’s father intended to journey with some family members to a land Yahweh was very interested in, Canaan. Indeed, when God eventually called Abram, he told him to complete the journey his father had started. Understandably, Abram took everyone who began the journey with Terah with him to Canaan (Genesis 12:5). No reason is given for why God wanted Abram to complete the journey, but we are told the following:

Genesis 12:2-3 ESV

[2] And I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. [3] I will bless those who bless you, and him who dishonors you I will curse, and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed.”

This is a familiar passage that deserves careful parsing. Narratively, Genesis 10 describes the many nations that emerged from the three sons of Noah. Strangely, God calls Abram and promises to make a hitherto non-existing great nation out of him, even though several great nations already exist on earth. In fact, Abraham did not even have a child because his wife was barren. It is as though God abandoned the other nations to start afresh with Abram. He, however, is not permanently abandoning the other nations because “all the families of the earth” somehow will be blessed by the nation God would make of Abram. From that moment forward, God specifically guarded the blessing within Abram’s lineage.

This was a serious project because God clarified that he needed no help. Abram was 75 when God called him and told him he would become a great nation, but he remained childless 10 years later. (This is a recurrent theme we have seen in Genesis so far – God never seems to be in a hurry.) So Abram (and Sarai) understandably thought they could help God initiate the “great nation” project through a second wife. But God was firm and clear:

Genesis 17:19-21 ESV

[19] God said, “No, but Sarah your wife shall bear you a son, and you shall call his name Isaac. I will establish my covenant with him as an everlasting covenant for his offspring after him. [20] As for Ishmael, I have heard you; behold, I have blessed him and will make him fruitful and multiply him greatly. He shall father twelve princes, and I will make him into a great nation. [21] But I will establish my covenant with Isaac, whom Sarah shall bear to you at this time next year.”

Ishmael was not it – hence, the later Islamic claim of a prophet from Ishmael’s lineage has no basis whatsoever in Scripture. Ishmael will also become a great nation like the ones in Genesis 10. But he is not to become the “great nation” that will be a blessing to the world.

Eventually, 25 years after the initial promise, the promised son Isaac was born. And when he became a father, he gave birth to twins, creating a little problem. The “great nation” lineage can not come from both children. God must make his election clear again. It would be Jacob, despite his devious ways. Jacob would become a father of 12 sons, but the promise must be carried forward through Judah, one of Jacob’s worst and most unintegral sons. Matthew states that God closely supervised the blessing for 42 literary generations until Jesus was born.

The Gospel Effectuated

This, then, is the long-lived redemption plan of God. Jesus was the long-awaited son and deliverer. This Messiah will decisively address all the problems we have discussed. Paul clearly understands this when he writes:

Galatians 3:8 ESV

And the Scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, preached the gospel beforehand to Abraham, saying, “In you shall all the nations be blessed.”

The good news, or gospel, of God finally redeeming the cosmos did not start with Jesus. On the contrary, Jesus came to initiate the end of it. The Gospel that Jesus effectuated began with Abraham. Abraham was the genealogical head of a project that produced the promised Rescuer of the cosmos. But the problems predated even Abraham. The Jesus Event finally effectively dealt with the problems we have chronicled: the glory lost in Eden, language confusion at Babel, and the corruption of the angelic sons of God.

Jesus as Adam 2.0+

Romans 5:12-21 is an extensive contrast of Adam and Jesus, which shows that Jesus’s appearance had something to do with the ancient problem in the garden:

Romans 5:12-15 ESV

[12] Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all sinned— [13] for sin indeed was in the world before the law was given, but sin is not counted where there is no law. [14] Yet death reigned from Adam to Moses, even over those whose sinning was not like the transgression of Adam, who was a type of the one who was to come. [15] But the free gift is not like the trespass. For if many died through one man’s trespass, much more have the grace of God and the free gift by the grace of that one man Jesus Christ abounded for many.

The argument is straightforward: Jesus reverses the error and the attending consequences of Adam’s trespass in the Garden. Whereas death, through sin, spread to all men as a result of Adam’s acts, Jesus’s obedience provides life to all who appropriate the offer:

Romans 5:18-19 ESV

[18] Therefore, as one trespass led to condemnation for all men, so one act of righteousness leads to justification and life for all men. [19] For as by the one man’s disobedience the many were made sinners, so by the one man’s obedience the many will be made righteous.

Hence, Jesus solves the Adam Problem. Christ is the second and last Adam (1 Corinthians 15:45, 47).

Tongues in Acts: Babel Reversed

Luke, the author of Acts, seems intentional about connecting the ministry of Jesus – specifically the ministry of the Holy Spirit – to the Babel event of Genesis 11, thereby implying that Jesus addresses another ancient problem. Below is how the Babel story begins:

Genesis 11:1-4 ESV

[1] Now the whole earth had one language and the same words. [2] And as people migrated from the east, they found a plain in the land of Shinar and settled there. [3] And they said to one another, “Come, let us make bricks, and burn them thoroughly.” And they had brick for stone, and bitumen for mortar. [4] Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves, lest we be dispersed over the face of the whole earth.”

The chapter begins by saying the whole world had one language. Since the previous chapter gives a table of nations, each with its own language (Genesis 10:5), we need not conclude that this verse asserts the existence of a single language from which all languages are derived – a claim against current scientific evidence. On the contrary, the verse can be taken to say the world had a lingua franca, a common language for business. The relevant point here is the flow of this narrative: the people had a common language and understanding to permanently station at a chosen spot rather than spread all over the earth as God wanted. To achieve his goal, God determined that confusing their language so they no longer understand one another was an effective way to get the people to abandon the project (Genesis 11:7, 9).

In Acts 2, the believers were gathered in one spot as Jesus instructed them. Suddenly, the Spirit descended and filled eachperson so that they “began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit gave them utterance” (Acts 2:4). Meanwhile, something else was happening outside:

Acts 2:5-12 NIVUK

[5] Now there were staying in Jerusalem God-fearing Jews from every nation under heaven. [6] When they heard this sound, a crowd came together in bewilderment, because each one heard their own language being spoken. [7] Utterly amazed, they asked: ‘Aren’t all these who are speaking Galileans? [8] Then how is it that each of us hears them in our native language? [9] Parthians, Medes and Elamites; residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, [10] Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya near Cyrene; visitors from Rome [11] (both Jews and converts to Judaism); Cretans and Arabs – we hear them declaring the wonders of God in our own tongues!’ [12] Amazed and perplexed, they asked one another, ‘What does this mean?’

Religious Jews from “every nation under heaven” heard the Galileans speak in these traveling Jews’ languages. Both the “every nation under heaven” phrase and the list of nations provided allude to Genesis 10, the table of nations, and Genesis 11. And, of course, the central action is a reversal. Unlike in Genesis 11, God has supernaturally enabled all the people “from every nation under heaven” to once get his message through “common” languages.

Acts expands the pattern. Every time a distinct category of people received the gospel message, they spoke in tongues. This happens again in Acts 10 at Cornelius’ house – the first Gentile group to be accepted by God without first converting to Judaism. In Ephesus, a region far removed from the regions of the Spirit’s operations thus far in Acts, some individuals also received the Spirit and spoke in tongues. This suggests that the divine program is not geographically restricted.

The Death of Jesus and the Powers

We have been trained over the years to associate Jesus’s death with the atonement – and, for sure, it has much to do with that. But the death of Jesus addresses other critical issues. Consider the following:

Colossians 2:13-15 ESV

[13] And you, who were dead in your trespasses and the uncircumcision of your flesh, God made alive together with him, having forgiven us all our trespasses,

[14] having cancelled the charge of our legal indebtedness, which stood against us and condemned us; he has taken it away, nailing it to the cross. [15] And having disarmed the powers and authorities, he made a public spectacle of them, triumphing over them by the cross.

This common passage deserves careful parsing. The central issue the letter to the Colossians addresses is the sufficiency and supremacy of Christ for salvation. The Colossian church was being harassed by some Jewish teachers teaching that the Gentile church had to do more to become complete children of God. The “more” required seemed to be about Jewish mysticism and Torah-observing. Paul would have none of that as he revealed the clearest and boldest claims about Jesus (Colossians 1:15-21; 2:9-11). In Colossians 2:8, Paul writes:

Colossians 2:8 ESV

See to it that no one takes you captive by philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the world, and not according to Christ.

In this difficult verse, Paul contrasts Christ with some “elemental spirits of the world.” According the the Faithlife Study Bible, there are three possibilities for the “elemental spirits”:

The Greek phrase used here could refer to several concepts: the basic religious teachings of Jews and Gentiles; the material parts of the universe (such as water, earth, and fire); or spiritual powers (such as evil spirits or demonic entities). In this context, the first and third options are most likely. Paul makes clear that these teachings or forces are negative influences.

In other words, Paul says the mystical Jewish doctrines are being influenced by demonic forces in opposition to Christ. This is the context for understanding 2:13 – 15. Verse 15 says Jesus disarmed the “powers and authorities” and “made a public spectacle of them, triumphing over them by the cross.” In other words, Jesus’s death on the cross, while initiating the atonement process, was a direct victorious battle over the powers and authorities, the elemental spirits of the world who influenced the lives of the Gentiles (See Colossians 2:20). How is that so?

A Return to Bashan

As argued at length in another entry, Jesus’ statement in Matthew 16 is directly connected to this idea:

Matthew 16:18-19 ESV

[18] And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. [19] I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.”

The Gospels record Jesus once making a 25-mile-and-15-hour trip from Galilee to Caesarea Philippi, where Jesus uttered the words above (See Matthew 16:13). But “Caesarea Philippi” was a new name for an ancient rocky region we have already encountered, Bashan. (See our “Gates of Hell” article for how Bashan became Caesarea Philippi.) Besides, at the time of this trip in the first century, this region had a temple devoted to Pan, the god of the underworld. It also had a grotto locals described as the “gates of Hades.” Matthew employs much wordplay in verse 18. “Peter” means “rock,” and Jesus uttered the words while he stood on a rocky surface. In other words, Jesus here declared that he would build his church right atop the gates of Hades, thereby employing another double entendre. He referred to the spiritual reality of Hades while affirming that Peter would play a critical role in the project.

Furthermore, this battle with Hades will somehow result in Jesus giving the keys of the kingdom of heaven to Peter (and the rest of the disciples). The Apostles had a gatekeeping role in the kingdom. It is, hence, not an accident that when the church’s construction properly began with the giving of the Holy Spirit in Acts 2, Peter gave the first public sermon. Notice how Matthew immediately connects the “gates of Hell” pericope with the death of Jesus:

Matthew 16:21 ESV

From that time Jesus began to show his disciples that he must go to Jerusalem and suffer many things from the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed, and on the third day be raised.

Matthew here tells us that everything Jesus said hinged on his death.

As earlier shown, Paul also connects Jesus’s death and Bashan. When Jesus took the disciples to Caesarea Philippi, Paul was not yet a believer. But after Jesus appeared to him, Paul validates the “gates of Hades” story through Psalm 68. Paul repurposes Psalm 68 in Ephesians 4:8 – 14. Paul’s use of Psalm 68 implies that giving ministry gifts – Apostles, Prophets, Pastors, Evangelists, and Teachers – to the church is a continuation of the church-building process Jesus said he would perform atop Bashan. Paul specifically says these gifts are “for building up the body of Christ” (Ephesians 4:12). The “body of Christ” is, of course, the church. In other words, Jesus’s one-time mission to Caesarea Philippi continues to bear fruit through ministry gifts. God continues to settle an old score, as Psalm 68 prophecies. Jesus is the Yahweh who settles the score.

John the Revelator also alludes to this reality. The resurrected Jesus introduces himself to John in this way:

Revelation 1:17-18 ESV

[17] When I saw him, I fell at his feet as though dead. But he laid his right hand on me, saying, “Fear not, I am the first and the last, [18] and the living one. I died, and behold I am alive forevermore, and I have the keys of Death and Hades.

When and where did Jesus get “the keys of Death and Hades”? Obviously, when he died and went to the Underworld. The imagery here is of a complete routing of his enemies. He beat them so badly that he took the keys from them. They no longer can keep people in, but Jesus can keep people out of the reach of Death and Hades. As John records, Jesus’s encounter with Hades was a victory useful for encouraging believers:

Revelation 3:21 ESV

The one who conquers, I will grant him to sit with me on my throne, as I also conquered and sat down with my Father on his throne.

But, of course, believers are not expected to do battle in life by themselves or in their own strength. Indeed, there is another related reason Jesus died and rose:

Hebrews 7:24-25 NIVUK

[24] but because Jesus lives for ever, he has a permanent priesthood. [25] Therefore he is able to save completely those who come to God through him, because he always lives to intercede for them.

Right now, Jesus is praying for his own. His love for humanity is deep. When it is all said and done, God will dwell with humans in a new Eden, just he wanted always wanted:

Revelation 21:3-7 ESV

[3] And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “Behold, the dwelling place of God is with man. He will dwell with them, and they will be his people, and God himself will be with them as their God. [4] He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning, nor crying, nor pain anymore, for the former things have passed away.” [5] And he who was seated on the throne said, “Behold, I am making all things new.” Also he said, “Write this down, for these words are trustworthy and true.” [6] And he said to me, “It is done! I am the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end. To the thirsty I will give from the spring of the water of life without payment. [7] The one who conquers will have this heritage, and I will be his God and he will be my son.

And this, all of this, is the gospel. This the good news that turned the ancient world upside down and brought a great empire to its knee.

Work Cited

Barry, John D., Douglas Mangum, Derek R. Brown, Michael S. Heiser, Miles Custis, Elliot Ritzema, Matthew M. Whitehead, Michael R. Grigoni, and David Bomar. 2012, 2016. Faithlife Study Bible. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press.